|

Introduction:

The Undercounting of Minorities in the United States Census

It

is not possible to count fully and accurately the population of a large and

diverse nation. No matter how heroic their efforts, census takers inevitably

miss some persons who should be counted. Other persons may be double-counted

and the enumeration process itself may erroneously add persons to the count.

The net undercount is the difference between persons missed in the census

and persons double-counted or erroneously included.3 Since 1940,

the Census Bureau has acknowledged a net undercount that is not randomly distributed

across the population. The undercount, measured in percentage terms, is substantially

larger for minorities than for whites. The differential undercount for minorities,

moreover, is not a function of the total undercount in the population. In

1940, the net undercount for the population was 5.4 percent, compared to less

than 2 percent for 1980 and 1990. Yet the differential undercount of about

4 percentage points between whites and non-whites has not varied significantly

during this 50-year period.4

Traditional

census procedures are not effective in reducing the differential undercounting

of whites and minorities. According to recent studies conducted by two panels

of the National Academy of Sciences, "differential undercounting cannot

be reduced to acceptable levels at acceptable costs without the use of integrative

coverage measurement," which is a statistical sampling method that adjusts

census data for the undercount. Three panels of the National Academy of Sciences

recommended including such an adjustment in order to create the most accurate

possible census and to reduce the differential undercounting of whites and

minorities.5

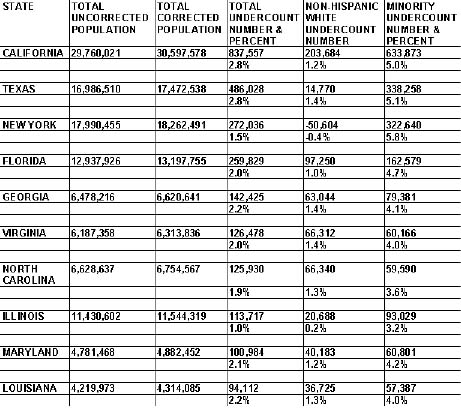

Although

census data corrected for such statistical sampling were not included in the

official data released for redistricting purposes in 1991, the Census Bureau

did eventually report the corrected numbers, which substantially reduced the

undercounting of minorities. Table 1 demonstrates that for each state studied,

the percentage undercount of members of minority groups is substantially higher

than the percentage undercount of non-Hispanic whites. In one state _ New

York _ the 1990 Census even slightly overcounted non-Hispanic whites, despite

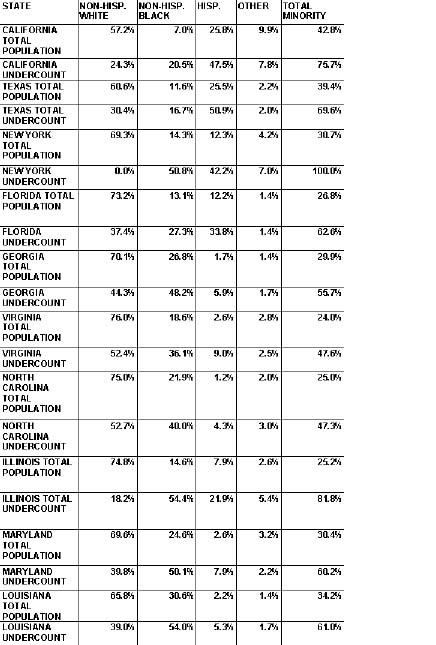

undercounting members of minority groups. Table 2 demonstrates that the undercounted

population in each instance includes a much greater percentage of minorities

than a state's overall population.

The

failure to adjust for the undercounting of minorities in the drawing of legislative

districts can affect opportunities for minority voters to participate fully

in the electoral process and elect candi dates of their choice to legislative

positions. Differences in the numbers and percentages of minorities can be

significant in areas of minority concentration, where legislative districts

with substantial percentages of minorities are drawn. Given differences in

the candidate preferences of white and minority voters, small differences

in the minority composition of districts can be consequential for the opportunity

for minorities to elect candidates of their choice in such districts.

TABLE

1.

The state-by-state analysis that follows below will explore the implications

for minority voter opportunities of using corrected as opposed to uncorrected

data from the 1990 Census. At the time of the completion of this report, the

Census Bureau had not yet released the block level data used for the post-2000

redistricting and other purposes. Existing legislative districts, however,

serve as a baseline against which to assess minority voter opportunities when

new districts are created in each state. For those involved in drawing redistricting

plans, the 1990 experience can also be an important guide for assessing the

impact on minority voter opportunities of the use of corrected versus uncorrected

data for the post-2000 redistricting.

This analysis will

not attempt to redraw legislative district plans or demonstrate that a shift

to corrected data in the post-1990 redistricting process would necessarily have

produced different configurations of districts. It does not suggest that districts

should be based primarily on race. It does not attempt to reassess comprehensively

the redistricting plans of the states included in the study. No claim is made

here that the districts identified in the state-level analyses are the only

ones in which there had been a potential to enhance minority-voting strength.

Rather the analysis explores only whether the use of corrected data would have

had the potential to expand minority voter opportunities in the post-1990 redistricting.

The analysis is limited to plans drawn statewide for Congress, State Senates

and State Houses of Representatives. It should be noted, however, that as compared

to such statewide redistricting plans, the use of corrected census data would

likely have had an even greater potential impact on the relatively less populous

districts drawn for municipal and county governments within each state. The

web site of the National Committee for an Effective Congress (NCEC) provides

data on the demographic composition of each state's congressional, state senate,

and state house districts.6 For states that have altered their district

plans during the 1990's, the NCEC data is for the most recently available plan.

District maps are available from the NCEC and from the web sites of most state

governments.

|

|

|