Appendix A: Citizens’ Health Care Working Group Community Meetings: Overview of Local Demographics and Health Resources

Appendix B: Summary of Community Meeting Data

Appendix C: Working Group Health Care Poll

Appendix D: University Town Hall Survey

Appendix E: Health Care Presentations

Appendix F: National Health Care Polls and Survey Reports Related to the Working Group Analyses

Appendix G: Public Comments on Interim Recommendations

How We Did Our Work

Hearings

In the summer and early fall of 2005, the Working Group held hearings in Crystal City, Virginia; Jackson, Mississippi; Salt Lake City, Utah; Houston, Texas; Boston, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon to learn about the nation’s health care system. At the first hearings, health policy experts provided a common foundation on topics including employer-based and other private insurance, public programs including Medicare and Medicaid, health care costs, and public and private initiatives to control costs and expand insurance coverage. At the subsequent hearings topics included: the uninsured and underserved, health care quality, geographic variation in health care utilization, health information technology, rural health issues, mental health, health care disparities, long-term care, end-of-life care, community-based care, and Oregon’s experience in public engagement on health care issues.

We also heard of many private and public programs trying to expand access to care, improve quality, and reduce costs. Some of the programs we heard about were state and local programs to expand health insurance coverage; employees and employers working together to expand access by holding costs down and getting the right care at a good price; using health care technology to reduce medical errors, monitor patient care, and choose the most appropriate care for patients; providing more information to providers and patients for making choices about health care; encouraging people to use less expensive but equally effective care such as generic drugs; adjusting payments to doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers based on the quality of care they provide; and improving people’s access to care and insurance coverage through more effective use of current programs or new programs that will allow small business and self-employed individuals to obtain coverage.

Many of the programs are new, so we don’t know yet how well they will work over the long term. And, because these programs were designed to work in particular places, we don’t know whether the programs would fit, or work successfully, in other locations or settings. However, the hearings reinforced our conclusion, as stated in the Health Report to the American People, that we need to address the entire health care system, not just specific problems in cost, quality, or access, no matter how urgent they may seem from our different perspectives. Ideally, savings gained from improving efficiency and quality in the system could be used to make other needed changes. Some of the proposed health care initiatives could help to keep the amount and type of some health care services we receive the same, while controlling costs and improving quality. But we also concluded that none of the initiatives that we reviewed could provide all the answers to our health care system’s problems. Rather, the hearings helped lay the groundwork for the search for solutions described in this report.

A complete list and brief description of the 61 presentations made by experts at these hearings is found in Appendix E.

Public Dialogue

The Working Group conducted community meetings throughout the United States to hear from, and begin a dialogue with, the American people. As stated in the statute, these meetings constitute the primary source of input that the Working Group has used in developing its preliminary recommendations. In addition, however, a variety of complementary forms of input (described below) have been important. These different types of input were designed to engage a broad segment of the American public in an informed discussion, using formats that allowed both

-

free expression of all views, and

-

sufficient structure to allow the Working Group to characterize and compare different views in order to reach conclusions based on the dialogue.

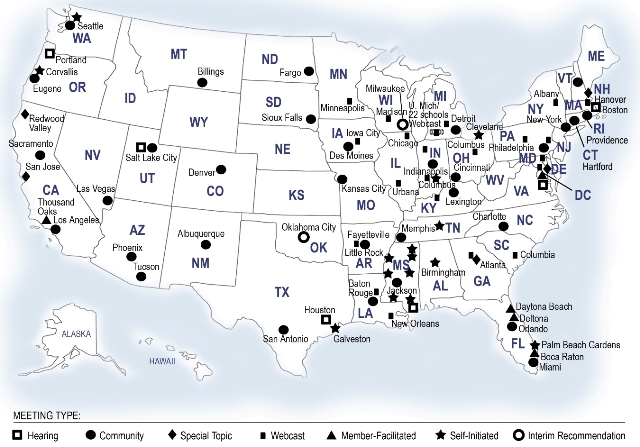

Working Group Community Meetings

The Working Group conducted 31 Community Meetings in 28 states between January and May 2006 (see Appendix A). These meetings ranged in size from about 35 to approximately 500 participants. At least one Working Group Member attended each meeting. Each meeting was organized using one of a set of formats designed for meetings of different lengths, but all were based on discussion of the four questions to the American people posed in the legislation. The discussion guides, as well as other background materials developed for the meetings (videos, slides, etc.), were all based on the analysis of issues confronting the American health care system presented in the Working Group’s publication, The Health Report to the American People, with some updated facts and figures. Audience generation for the community meetings consisted of outreach through both earned and paid media, involvement of national and local organizations, associations, and other groups, and the participation of various leaders and government officials at the local, state and national levels. Professional meeting facilitators led the meetings.

The basic structure of the meetings involved discussion among participants sitting in small groups, and a structured process for reporting the views of the groups. At the 31 Community Meetings, electronic devices allowed individuals to provide responses to all or some of the same questions included in the poll posted on the Working Group Internet site (see Appendix C), and used in other polls and surveys. The responses to each question were then displayed on a screen, providing immediate feedback to the participants. As discussed in "The Dialogue" (below), there was some variation in the wording of the "standard" questions from meeting to meeting, in response to the preferences of the groups. The format therefore allowed participants to alter the discussion when they felt it was important to do so, while providing enough consistency to allow for comparisons on key issues. Attendees were also encouraged to provide written comments, and many did so. Staff of the Working Group also considered these comments in their review of the meetings.

Additional Meetings

Another important set of discussions took place at the University town hall meeting sponsored by the Big Ten Conference and the Association of Schools of Public Health, and hosted by the University of Michigan on March 22, 2006 (see Appendix D). This virtual town hall provided a forum for individuals gathered at 22 separate public meetings organized by the participating universities, along with the webcast of the meeting from the University of Michigan, as well as people viewing the live webcast across the country. Interactive technology allowed various locations to call in with questions and comments, and individuals submitted their feedback about health care in America through e-mail to be read to participants during the live event.

Still other meetings organized by individual Working Group Members and staff in collaboration with community based health, advocacy, and business groups provided additional insights and opportunities to hear from people with perspectives that might not have been well represented at the other community meetings (see below). Some of these were directly related to issues that were raised in the hearings held by the Working Group (see Appendix E). These special meetings included sessions focusing on mental health, health care at the end of life, chronic illness and disability, a series of meetings in rural areas of Mississippi, a meeting co-hosted with Native American organizations, and a meeting organized by a national association representing realtors.

The Working Group also reviewed data from additional meetings that members as well as other people throughout the country conducted on their own, using materials developed by the Working Group and made available to the public in the "Community Meeting Kit" available on the web site. A listing of meetings that have provided data to the Working Group is included at the end of this section. Other organizations have also provided us with information. Among these are: The National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), which conducted a nationwide outreach effort to gather the input of homeless persons; data from the responses of 446 homeless persons in 12 cities were provided to the Working Group.

Other Direct Citizen Input

The Working Group solicited input from people across the country via the Internet, at www.citizenshealthcare.gov, and by mail.

The Working Group Public Comment Center on its web site solicited both structured and unstructured comments from the public.

-

"What’s Important to You" sought responses to four broad questions about people’s concerns about health care in America, views on changing the way health care is delivered or paid for, trade-offs that people would be willing to make to improve health care, and recommendations that people would make to improve health care for all Americans. The responses submitted by over 4,600 people from across the United States were coded into response categories and analyzed. The full text of close to 2,200 hand written responses was also provided to the Working Group for review. The United Church of Christ provided us with about 1,500 hand-written responses from people in about 10 percent of its 5,700 churches across the country to the open-ended questions posted on our Internet site; these are included in our analysis.

-

Close to 600 people wrote to the Working Group, via the CHCWG Internet "Share Your Experience" page or in handwritten letters, to tell us about their own stories. Many of these described problems obtaining or paying for adequate health insurance or quality health care; some described very positive experiences with the health care system.

-

The Health Care Poll posted on the web site drew over 13,000 responses from January through August 31 (see Appendix C). The Catholic Health Association (CHA) also provided over 1,000 poll responses that were submitted directly to CHA’s web site. These are included in the analysis of poll data; the responses are also presented in Appendix C. A number of organizations, including Communication Workers of America (CWA), Starbucks Coffee Company, The National Health Law Program, the National Assembly on School Based Health Care, Wheaton Franciscan HealthCare, and the American Nurses Association also provided information and links to encourage people to provide input to the Working Group. Many people affiliated with these groups participated in community meetings and via the Internet. More than 500 members of the CWA responded to the Internet poll (see Appendix C). Additionally, many of the organizations that conducted their own meetings sent us paper polls. The Area Agency on Aging in Florida provided about 50 poll responses from seniors in Florida. Written input mailed to the Working Group was coded and analyzed using the same protocols as the electronic data submitted over the Internet.

Analysis of the Data

Methods

The Working Group reviewed summaries of all the sources described above. The Community Meetings were considered, for analytical purposes, as case studies. In addition to the data on demographics and the votes recorded at each meeting, staff reviewed background information on each location and, in the course of planning each meeting, obtained a great deal of information on the health care, resources, and policy issues in each community. Senior staff members who attended the meetings used a structured format when preparing the meeting reports. The individual reports, including the data recorded at each meeting, are being made available to the public on www.citizenshealthcare.gov. The Working Group compared data across meetings only when it was truly comparable, that is, questions were asked in the same context during the meetings, in the same form. (See Appendix B for more information.)

Staff coded and analyzed data from open-ended, on-line polls, and Interim Recommendation responses using standard statistical software. The Working Group reviewed summary data, as well as the results of analyses that reflected possible differences in response patterns related to demographic differences. The Working Group also reviewed data from relevant national polls and surveys.

Public Comments

The Interim Recommendations posted on the web site received over 8,000 responses, mostly via the Internet, but also by mail, from June 1 through August 31. These public comments were classified into response categories and analyzed; comments were also posted on the web site. Official feedback from advocacy organizations and professional associations were reviewed by the Working Group members as well as staff, and posted on the Working Group web site. A summary of the comments and the Working Group’s response to the comments is presented in Appendix G.

Limitations

People attending the Working Group Community Meetings or providing input in writing are more likely than others to be especially interested in health care, either because they, or their family members, have had concerns about their health care or insurance coverage, or because they work in the health care field. The people we heard from were, on average, more likely to be female and in or on the edges of the Baby Boom generation (age 45-64), and the proportion having bachelor degrees or advanced graduate degrees was much higher than in the population as a whole. And, while participation in Community Meetings by minority group members was fairly close to national percentages, representation of people who identified themselves as Latino or as African American among those submitting comments or poll data was lower. The proportion of people who were not covered by any form of health insurance, and the proportion receiving benefits through Medicaid, was also lower than the nation as a whole. Some of these limitations were addressed by holding meetings specifically designed to reach underrepresented populations (see above). And, as noted above, analysis of the data was performed to assess the extent to which demographic factors may have accounted for some of the findings.

A more serious issue is the inability to ensure that people providing input represent the full spectrum of views of all Americans, given that people who are sufficiently interested or motivated to provide input on health care and policy issues may not be typical of the population as a whole. The consistency of findings across many communities and between the poll data obtained through both the Working Group Internet site and the community meetings provides support for the view that we have heard from a significant segment of the American people. The consistency between findings from recent national polls and surveys provides even stronger support for the findings. However, the meetings, as well as the www.citizenshealthcare.gov data were designed to offer information to help frame discussion and responses to questions, whereas national polls and surveys generally do not serve this purpose. Therefore, the responses we have analyzed are not exactly comparable to other national poll data, even when the same, or very similar, questions are asked. Consequently, we do not claim that we know, with great certainty, the values and preferences of all Americans. Rather, we are basing our recommendations on a careful assessment of input from as many sources as feasible, from tens of thousands of people from all across the United States, taking into account the gaps or biases that may be reflected in the data to the best of our ability.

Working Group Community Meetings (table)

| Kansas City, MO |

January 17, 2006 |

| Orlando, FL | January 24, 2006 |

| Baton Rouge, LA | January 26, 2006 |

| Memphis, TN | February 11, 2006 |

| Charlotte, NC | February 18, 2006 |

| Jackson, MS | February 22, 2006 |

| Seattle, WA | February 25, 2006 |

| Denver, CO | February 27, 2006 |

| Los Angeles, CA | March 4, 2006 |

| Providence, RI | March 6, 2006 |

| Miami, FL | March 9, 2006 |

| Indianapolis, IN | March 11, 2006 |

| Detroit, MI | March 18, 2006 |

| Albuquerque, NM | March 20, 2006 |

| Phoenix, AZ | March 25, 2006 |

| Hartford, CT | April 6, 2006 |

| Des Moines, IA | April 8, 2006 |

| Philadelphia, PA | April 10, 2006 |

| Las Vegas, NV | April 11, 2006 |

| Eugene, OR | April 18, 2006 |

| Sacramento, CA | April 19, 2006 |

| San Antonio, TX | April 19, 2006 |

| Billings, MT | April 21, 2006 |

| Fargo, ND | April 22, 2006 |

| New York, NY | April 22, 2006 |

| Lexington, KY | April 25, 2006 |

| Cincinnati, OH | April 29, 2006 |

| Little Rock, AR | April 29, 2006 |

| Tucson, AZ | May 4, 2006 |

| Sioux Falls, SD | May 6, 2006 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | May 6, 2006 |

University Town Hall Meeting, March 22, 2006 (table)

| Participating Institutions* | |

| Boston University | Boston, MA |

| Drexel University | Philadelphia, PA |

| Emory University | Atlanta, GA |

| George Washington University | Washington, DC |

| Indiana University | Indianapolis, IN |

| Johns Hopkins University | Baltimore, MD |

| Louisiana State University | Baton Rouge, LA |

| Michigan State University | East Lansing, MI |

| Northwestern University | Evanston, IL |

| Ohio State University | Columbus, OH |

| Penn State University | Harrisburg, PA |

| Purdue University | West Lafayette, IN |

| Tulane University | New Orleans, LA |

| University at Albany | Albany, NY |

| University of Arkansas | Fayetteville, AR |

| University of Illinois | Urbana, IL |

| University of Iowa | Iowa City, IA |

| University of Louisville | Louisville, KY |

| University of Michigan (Host) | Ann Arbor, MI |

| University of Minnesota | Minneapolis, MN |

| University of South Carolina | Columbia, SC |

| University of Wisconsin | Madison, WI |

* Not all meetings took place at main campuses.

Special Topic Community Meetings (table)

| Hanover, NH | Last Days | March 31, 2006 |

| Redwood Valley, CA | Native Americans | April 20, 2006 |

| Washington, DC | National Association of Realtors | May 16, 2006 |

| Atlanta, GA | Mental Health | May 22, 2006 |

Meetings Organized/Facilitated by Individual Members (table)

| Washington, DC | Ascension Health CEOs | December 5, 2005 |

| Daytona Beach, FL | Bethune-Cookman College | March 26, 2006 |

| Deltona, FL | Florida CHAIN (Community Health Action Information Network) and MS-keteers Multiple Sclerosis Support Group | May 6, 2006 |

| Palm Beach Gardens, FL | Area Agency on Aging | May 10, 2006 |

| Boca Raton, FL | Area Agency on Aging | May 11, 2006 |

| Lake Worth, FL | Area Agency on Aging | May 12, 2006 |

| Thousand Oaks, CA | City of Thousand Oaks Conejo Recreation and Park District | May 18, 2006 |

| Miami, FL | The Alliance for Human Services, The Human Services Coalition, Florida CHAIN, Miami-Dade County Health Department, Health Foundation of South Florida | August 22, 2006 |

Self-Initiated Meetings (table)

| Crossville, TN | The Learning Community | January-March, 2006 |

| Galena, IL | League of Women Voters | February 23, 2006 |

| Starkville, MS | MSU Extension | March 21, 2006* |

| Verona, MS | MSU Extension | March 27, 2006* |

| Wesson, MS | MSU Extension | March 29, 2006* |

| Hattiesburg, MS | MSU Extension | March 30, 2006* |

| Clarksdale, MS | MSU Extension | April 11, 2006* |

| Palm Beach Gardens, FL | Human Resource Association of Palm Beach County | April 11, 2006 |

| Greenville, MS | MSU Extension | April 18, 2006* |

| Newton, MS | MSU Extension | April 20, 2006* |

| Cloverdale, CA | United Church of Cloverdale | April 23, 2006 |

| Eau Claire, WI | Chippewa Valley Technical College | April 29, 2006 |

| Seattle, WA | Association of Advanced Practice Psychiatric Nursing | April 29, 2006 |

| Alpena, MI | League of Women Voters | May 1, 2006 |

| Galveston, TX | Center to Eliminate Health Disparities, University of Texas Medical Branch | May 1-3, 2006 |

| Boulder, CO | Individuals | May 3, 2006 |

| McKeesport, PA | Mon Valley Unemployed Committee | May 11, 2006 |

| Muncie, IN | BMH Foundation and Partners for Community Impact | June 2, 2006 |

| Birmingham, AL | Greater Birmingham PDA/DFA, UFCW Local 1657 | June 22, 2006 |

| Corvallis, OR | Mid Valley Health Care Advocates |

July 20, 2006 |

| Birmingham, AL | Birmingham Friends Meeting | July 16, 2006 |

| Jackson, MS | MSU Extension | August 22, 2006* |

| Hattiesburg, MS | MSU Extension | August 23, 2006* |

| Greenville, MS | MSU Extension | August 24, 2006* |

| Cleveland, OH | North East Ohio Voices for Health Care | August 24, 2006 |

| Columbus, IN | Columbus Regional Hospital Foundation (2) | August 29, 2006 |

* Held under the auspices of the Mississippi State University Extension Service.

Community Meetings on Interim Recommendations (table)

| San Jose, CA eBay/PayPal |

July 20, 2006 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | August 1, 2006 |

| Milwaukee, WI | August 12, 2006 |

Locations of Community Meetings Across the United States (map)

The Dialogue

This chapter highlights public input on the four questions Congress specified that the Citizens’ Health Care Working Group ask the American people. The Working Group has reviewed all input it has received from community and other meetings, by Internet, by mail, in person, or by phone. Particular emphasis in this section has been given to information gathered in community meetings held throughout the nation, which Congress directed the Working Group to conduct before preparing its Interim Recommendations. Other survey data sources are discussed throughout this section, and they will also be highlighted in the Final Recommendations to Congress.

This chapter follows the organization of the "typical" meeting, which always began with a discussion of participants’ underlying values. The 31 community meetings varied slightly from site to site, reflecting differences in the participants’ interests and preferences. While the general structure of the meetings was similar, it evolved over time as the Working Group attempted to find more effective ways to gather the desired information. Meetings varied in length, with most meetings either three or four hours long, although some were shorter and a few longer. At all these meetings, discussions centered on the four legislatively mandated questions:

I. What health care benefits and services should be provided?

II. How does the American public want health care delivered?

III. How should health care coverage be financed?

IV. What trade-offs are the American public willing to make in either benefits or financing to ensure access to affordable, high-quality health care coverage and services?

Summary of Findings

The following common themes emerged from the community meetings and other sources of information collected from the American public by the Working Group:

Values

-

Underlying the discussion of the four legislative questions is the belief by virtually everyone in attendance at each community meeting that the health care system has at least some serious problems.

-

Over 90 percent of participants at community meetings and respondents to the Working Group’s poll believed that it should be public policy that all Americans have affordable coverage.

I. What health care benefits and services should be provided?

-

A clear majority of participants preferred that all Americans receive health care coverage for a defined level of services.

-

People at the community meetings frequently expressed strong support for increased focus on wellness and prevention services as part of "basic" coverage, rather than focusing only on treating sickness.

-

Participants at meetings continually emphasized the importance of a strong education component in health care and the management of health.

-

Individuals voiced support for a fairly comprehensive basic benefit design.

-

Although many participants recognized the need to do more to ensure that the health care provided is appropriate and delivered efficiently, they were also concerned about arbitrary limits on coverage and were not comfortable with bare-bones benefit packages.

-

Despite the reluctance of many to limit benefits, participants at meetings supported limiting coverage to services that have proven medical effectiveness.

-

Participants expressed some level of support for the idea that some people could pay for additional services outside the basic benefit package.

-

People wanted consumers to play an important role in deciding what should go into a basic benefit package.

-

Participants in some meeting sites discussed a potential role for a local board or other quasi-governmental entity in defining the basic level of services.

-

Participants expressed the desire to be involved in the management of their own health care and were willing to accept some responsibility for their medical decision-making.

II. How does the American public want health care delivered?

-

At the community meetings, individuals asked for a delivery system that is secure, transparent, easy to navigate, and treats the "whole person."

-

Affordability of care is a primary concern among participants.

-

Participants were troubled that many people did not have access to the health care they need.

-

Many participants cited complexity of the system as a contributing factor to the problems with the health care system.

-

Linked to confusion about the health care system was the lack of useful information to help individuals navigate the health care system.

-

Participants mentioned that they or others were not always treated with respect or dignity.

-

Participants frequently cited barriers to care related to their insurance coverage.

-

Participants told the Working Group that they want to feel secure knowing that when they or their families need care, they can get it without becoming impoverished.

-

Participants wanted all Americans to be able to get the right health care, at the right time, in a respectful manner.

-

Participants noted that being able to choose and maintain a stable, long-term relationship with a personal health care provider was critical.

III. How should health care coverage be financed?

-

Although the results differed across meeting sites, a majority of participants (ranging from 55 percent to 88 percent in the community meetings) believed that everyone should be required to enroll in either private or public "basic" health care coverage.

-

In almost every community meeting, a majority of participants supported the notion that some individuals should be responsible for paying more for health care than others. The most commonly mentioned criterion for paying more was income, but varying payment by income was supported by the majority of participants in fewer than half of the meetings where this question was discussed.

-

Views about employer-based coverage did not generally reflect a deep distrust of employers, but instead were intertwined with broader concepts of health reform.

-

At most meetings, participants stressed the importance of preventive care to reduce health care costs.

-

Participants at most meetings believed that individuals have a responsibility to manage their own care and use of services.

-

In many meetings, participants mentioned that individuals have a social responsibility to pay a fair share for health care.

-

Participants frequently stated that the problems of high costs rest with "price setters"—namely, prescription drug companies, insurers, and for-profit providers.

-

A commonly expressed view was that a simpler system would result in lower administrative costs.

-

Some support exists for investment by providers and the private sector in health information technology to increase system efficiency.

-

Participants expressed general support for individuals playing their part in controlling utilization and costs.

-

Individuals would like information about how to use health care better and more effectively.

-

At some meetings, participants supported providing incentives to patients to engage in healthy behaviors.

-

Participants expressed preferences for using medical evidence to decide which services are covered and provided.

-

There was general support for controlling prescription drug costs by limiting direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs and using more generic drugs, when medically appropriate.

-

Support also existed for limiting expensive yet "futile" end-of-life care and instead providing palliative care.

-

In almost all community meetings, participants expressed the belief that changing the culture from sick care to well care—namely, by focusing on prevention, wellness, and education (in general, and health education in particular)—will reduce health care costs.

-

A commonly expressed view was that better use of advanced practice nurses and other non-physicians could save money and improve quality.

-

Participants believed that investing in public health would pay dividends in terms of reducing health care costs.

-

Support for limits on malpractice was expressed at some community meetings.

IV. What trade-offs are the American public willing to make in either benefits or financing to ensure access to affordable, high-quality health care coverage and services?

-

In most meetings as well as on the Working Group poll, a majority of participants expressed a willingness to pay more to ensure that everyone has access to affordable, high-quality health care. Overall, about one in three (28.6 percent of poll participants) said they were willing to pay $300 or more per year.

-

When asked to rank or choose among competing priorities for public spending on health, individuals—with few exceptions—were most likely to rank "Guaranteeing that all Americans have health coverage/insurance" as the highest priority.

-

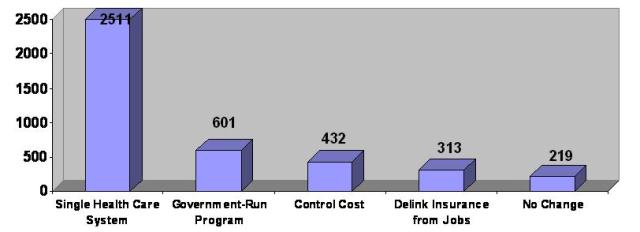

When asked to evaluate different proposals for ensuring access to affordable, high-quality health care coverage and services for all Americans, individuals at all but four meetings ranked "Create a national health insurance program, financed by taxpayers, in which all Americans would get their insurance" the highest. Three other options generally ranked in the top four choices at the community meeting locations: "Expand neighborhood health clinics"; "Open up enrollment in national federal programs like Medicare or the federal employees’ health benefits program"; and "Require that all Americans enroll in basic health care coverage, either private or public."

Detailed Description of Findings

Values

Before focusing on the four legislative questions, all meetings began with a discussion of individuals’ underlying values and perceptions that generally centered on three questions:

- When asked how they would describe the U.S. health care system

today, 97 percent of attendees across all community meetings selected

"It is in a state of crisis" (64 percent) or "It

has major problems" (33 percent). In each of the 31 community

meetings, at least 88 percent selected one of these options. Overall,

only two percent said "It has minor problems,"

and one percent either said "It does not have any problems"

or had no opinion. Underlying the discussion of the four legislative

questions is the belief by virtually everyone in attendance at each

community meeting that the health care system has at least some serious

problems. This same concern has also surfaced in national

polls. A January 2006 New York Times/CBS poll found that 90 percent

of respondents said that our health care system needs fundamental

changes or to be completely rebuilt (56 percent and 34 percent, respectively).1

This finding has been fairly consistent over the past 15 years. However,

the Employee Benefit Research Institute’s annual Health Confidencet

Survey has found from 1998 to 2004 the percent of respondents rating

our health care system as poor has doubled from 15 percent to 30 percent.

2

- When meeting participants at all meetings were asked, "Should

it be public policy that all Americans have affordable health care

coverage?", 94 percent overall said "yes." Similarly,

in the Working Group’s poll, 92 percent either strongly agreed

(79 percent) or agreed (13 percent) with this statement. Over

90 percent of participants at community meetings and respondents to

the Working Group’s poll believed that it should be public policy

that all Americans have affordable coverage. As stated by

participants in the Orlando community meeting, "Health care is

a right and not a privilege." Seattle, Denver, and Philadelphia

meeting participants, among other locations, desired "cradle

to grave" access to health care.

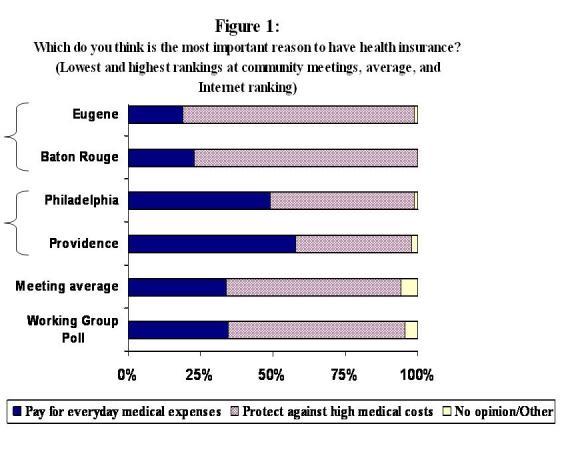

- At many of the community meetings, participants were asked what they believed was the most important reason to have health insurance. Although the results varied by meeting site, individuals were more likely to choose the response "To protect against high costs" than they were to choose the response, "To pay for everyday medical expenses."

Figure 1 illustrates how participants’ responses varied across community meeting sites and the Working Group poll.

Note: This question was not asked in Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Hartford, Las Vegas, San Antonio, Fargo, Lexington, Little Rock, or Sioux Falls. Eugene and Baton Rouge were the meeting sites where "Pay for everyday medical expenses" ranked as the lowest among the cities where the question was asked, while Philadelphia and Providence were the meeting sites where that option ranked as the highest. The meeting average reflects a weighted average of all meetings where this question was asked.

What health care benefits and services should be provided?

Some common themes have emerged from the community meetings regarding what health care benefits and services should be provided. In the community meetings, discussion of this question generally revolved around three core questions.

The first of these questions is discussed below:

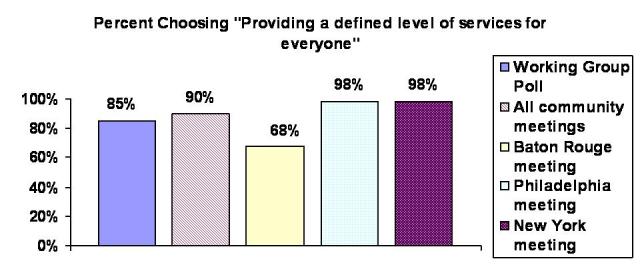

"Health care coverage can be organized in different ways. Two different models are: (1) Providing coverage for particular groups of people (e.g., employees, elderly, low-income) as is the case now; (2) Providing a defined level of services for everyone (either by expanding the current system or creating a new system). Which of the following most accurately reflects your views?"

In response to this question, a strong preference emerged:

-

A clear majority of participants preferred that all Americans receive health care coverage for a defined level of services. In response to the question, the vast majority (between 68 percent and 98 percent) of participants at all community meetings have said that we should provide a defined level of services for everyone. The highest level of support for a defined set of services was in the community meetings that were held in Philadelphia and New York, and the lowest in the Baton Rouge meeting (See Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Which statement best describes your views on how health care coverage should be organized?

In the Working Group poll, 84 percent of participants answered the question this way. These findings are also consistent with the results of other national polls asking similar questions. In surveys conducted by other organizations, a clear majority have expressed the opinion that all Americans should have health insurance. For example, a Wall Street Journal poll regarding public support for a range of health practices in September 2005 found that 75 percent of U.S. adults somewhat favored (23 percent) or strongly favored (52 percent) universal health insurance.3 More recently, a New York Times/CBS poll conducted in January 2006 found that 62 percent said that they think the federal government should guarantee health insurance for Americans; 31 percent said this was not the responsibility of the federal government, and 7 percent said they do not know. 4

Discussions at community meetings teased out variations in how people conceptualize health coverage. For example, some participants indicated that it was hard to make a choice between the answers without knowing who was providing the coverage, or what would be covered. Many tended to view access to health care as a basic right, and they conveyed a willingness to contribute to the success of a system that would facilitate health care for all.

-

In the Baton Rouge community meeting, where the smallest percentage of people opted for providing a defined level of services for everyone, participants still concluded that a defined level of services for everyone was "more fair and equitable" in the face of the current system that was "failing."

-

In the Detroit community meeting, some participants worried that the issue of discrimination needed to be addressed, regardless of the system design. Just like the current system of providing coverage for particular groups of people (such as Medicare or Medicaid for elderly, disabled persons or low-income populations, or group coverage organized through employment), a system providing a basic level of care for everyone ran the risk of not providing sufficient levels of care for all. Participants expressed concern that any system reform must avoid creating different levels of care for different subsets of the population.

-

At the two largest community meetings in Los Angeles and Cincinnati, fewer than 10 percent of participants favored the current system that provides coverage according to a person’s affiliation with a particular group. These participants, like those at the other meetings, cited problems with the current system, including:

-

It excludes the unemployed and others who are not part of a particular group

-

The system is high cost, complex, and not uniform across groups

-

Mobility and flexibility are a problem.

-

-

About 90 percent of participants supported the option of providing a defined level of benefits for everyone, rather than the current system of coverage for certain groups. The virtues of implementing a system of coverage for all that were mentioned included:

-

Reduced overall and administrative costs

-

Decreased hospitalization and emergency room use

-

Access for all

-

Covered prevention and immunization, and

-

Improved level of national health care.

-

However, participants also expressed potential concerns about such a system, such as: What is the defined level of services? Who will be denied access to care if costs are too high, and who will make these decisions? Who will pay?

-

At all locations, participants emphasized the importance of involving consumers in the development of a basic benefit package. Because consumers can articulate what services are necessary at various stages of life, their participation in the development of the plan could help contain costs. In the Phoenix community meeting, for example, participants wanted a basic plan that would vary based on age and gender, and that could be added to if desired. Participants at most meetings recognized that the current system does work for some, and allows for a richer benefit than might be available otherwise, but that it does not work for everyone. They expressed a desire to build upon the current system, changing it into something that is more inclusive and provides a level of care for all Americans. Everyone would contribute to this system based on their ability to pay. However, for those people who are unable to afford the cost, government subsidies should be provided to allow access to a basic package.

-

In the San Antonio community meeting, participants expressed interest in an approach that would provide a basic level of care for everyone combined with personal responsibility.

-

In a number of community meetings, including Lexington, Eugene, Sioux Falls, and Cincinnati, participants commented that the United States should learn from other countries that have covered all or most of their citizens.

The second structured question delved into how to define the specific level of benefits:

"It would be difficult to define a level of services for everyone. A health plan that many people view as ‘typical’ now covers these types of benefits, many of which are subject to co-payments and deductibles: preventive care, physicians’ care, chiropractic care, maternity care, prescription drugs, hospital/facility care, physical, occupational, and speech therapy, and mental health and substance abuse. How would a basic package compare to this ‘typical’ plan? Are there benefits that you would add or would take out?"

Although the discussion differed by meeting location, some common themes emerged:

- People at the community meetings frequently expressed strong

support for increased focus on wellness and prevention services as

part of "basic" coverage, rather than focusing only on treating

sickness. According to participants at meetings throughout

the country, individuals have a responsibility to be good stewards

of their health and health care resources (preventive care/screenings/use

of services). They also viewed an emphasis on wellness and prevention

services as a way to reduce health care costs, as discussed in the

Financing section. According to these participants, disease management

should also be a part of the focus. In the Working Group poll, over

90 percent of respondents indicated that annual physicals and preventive

care should be part of a "basic" or "essential"

benefits package, a level of support that was similar to that for

hospital stays, prescription drugs, and lab tests.

- Participants at meetings continually emphasized the importance

of a strong education component in health care and the management

of health. To be good stewards of their health, individuals

need to be educated about wellness and prevention. People thought

information about how to use health care better and more effectively

was important, but not information on cost. Broader issues of general

education also came up in some meetings. Participants talked about

the importance of beginning early, in grade school, to focus on basic

skills that are prerequisites to literacy and health literacy. Fargo

meeting participants expressed a preference for "school-based

health promotion programs" for those in kindergarten through

grade 12.

- Individuals voiced support for a fairly comprehensive basic

benefit design. Benefits that a number of participants in

meetings throughout the country viewed as important components of

a basic benefit package included—but were not limited to—dental

care, vision, hearing, care by non-physician providers such as nurse

practitioners, long-term care, mental health, and hospice care. Some

meeting participants also desired coverage of complementary and alternative

medicine (for example, acupuncture).

- Although many participants recognized the need to do more to ensure that the health care provided is appropriate and delivered efficiently, they were also concerned about arbitrary limits on coverage and were not comfortable with bare-bones benefit packages. A participant in the Eugene community meeting made the point, "There’s a need for definition because we can’t afford it all." Still, when pressed to make decisions about what services to drop from basic coverage, many respondents told the Working Group "None," which was the most popular response in some locations.

| "All people should have the same coverage

that the President, Vice President, and Congress have…" (Phoenix meeting) "We agree that there should be a basic level of services for everyone- everyone has a right to that care. But our concern is that neither of those--what we have now, or a basic plan for everyone-- will work until it’s a consumer-driven choice and not a corporate solution that values profits above everything else. The consumer should be driving the choices, not like the way the culture is now. There should be more of a balance." (Charlotte meeting) "Every citizen has a basic right to have basic health care, and it can’t be based on the type of job they have." (Salt Lake City meeting) |

- Despite the reluctance of many to limit benefits, participants at meetings supported limiting coverage to services to those that have proven medical effectiveness. They expressed a certain level of comfort with decisions that could affect utilization, if they were based on medical evidence. Just over half of the Working Group poll respondents agreed (36 percent) or strongly agreed (14 percent) that health plans or insurers should not pay for high-cost medical technologies or treatments that have not been proven to be safe and medically effective, and nearly a quarter were neutral on the subject; responses in the March University town hall meeting were similar (see text box below), with 58 percent agreeing (36 percent) or strongly agreeing (22 percent).

University Virtual Town Hall Meeting:

"A National Conversation on Health Care"

| On March 22, 2006, 22 universities participated

in a simultaneous discussion on health care. Sponsored by the Big

Ten Conference and the Association of Schools of Public Health,

and hosted by the University of Michigan, this virtual town hall

meeting provided a forum for individuals across the country to voice

their opinions on health care. Broadcast via satellite from the University of Michigan, individuals participated in this event either by gathering at various university sites, or by logging onto the forum through the Internet. Interactive technology allowed various locations to call in with questions and comments, and individuals submitted their feedback through e-mail to be read during the live event. The 21 simultaneous meetings held in addition to the host meeting were organized by their respective university communities, and followed the same format. Participants at these meetings received the standard Community Meeting Discussion Guide and a Health Care Poll, specific to this event, which included the majority of questions asked on the Working Group’s own Internet poll (as well as in many of the Working Group Community Meetings). The separate meetings also had access to a local faculty expert who assisted in sending comments and questions to the national coordinator at the University of Michigan. After the event, the completed Health Care Polls were coded (772 from 22 of the webcast sites) and entered into a data set that was made available to the Working Group for analysis (See Appendix D for a complete summary of the results). Participating schools were: Boston University Drexel University Emory University George Washington University Indiana University Johns Hopkins University Louisiana State University Michigan State University Northwestern University Ohio State University Penn State University Purdue University Tulane University University at Albany University of Arkansas University of Illinois University of Iowa University of Louisville University of Michigan University of Minnesota University of South Carolina University of Wisconsin |

- Participants expressed some level of support for the idea that some people could pay for additional services outside the basic benefit package. For example, in Kansas City, participants favored allowing individuals to purchase additional coverage of chiropractic care or fertility treatments. Charlotte participants were willing to pay more for an "a la carte" plan that would allow people to add services to the basic plan, which could vary by life phases and would be most cost effective for each age group. At virtually every meeting, attendees expressed concern about coverage for "futile" care at the end of life.

Results of the Working Group poll question about the importance of including each of 23 specific benefits can be found in Appendix C (Question 4 of the Working Group poll).

The next question in this section of the community meetings asked participants for their views on who should decide which benefits would go into the basic benefit package:

"How much input should each of the following groups have in deciding what is in a basic benefit package (federal government, state and/or local government, medical professionals, insurance companies, employers, consumers)?"

Some common themes emerged in response to this question:

- People wanted consumers to play an important role in deciding what should go into a basic benefit package. In meetings throughout the country, the majority of participants consistently answered that a combination of consumers, medical professionals, federal government, state and local governments—generally in that order—should be responsible for having input into these decisions. Some participants indicated that employers and insurance companies should also play a role, but one that is more limited.

In the majority of meetings, participants were asked, "On a scale of 1 (no input) to 10 (exclusive input), how much input should each of the following have in deciding what is in a basic benefit package?" When participants were asked the question in this way, the highest rating was always for input from consumers, and it was always followed by "medical professionals."

| "Some new entity or process needs to

be created that includes all the relevant stakeholders, the foremost

of which would be the consumer." "[There should be] a ‘quasi-governmental’ entity representing all groups, including us, the people." "One way to organize this would be to create an entity very much like the Federal Reserve Board with appointed individuals who are professionals in their field and whose activities are generally public so it has to come under the federal government but wouldn’t be the government as we generally think of it." (Orlando meeting) |

Responses to this question are illustrated in Figure 3. In some meetings and on the Working Group poll, individuals were asked which party or parties they would prefer to make the decision regarding what services are covered in the basic health insurance plan. At least 60 percent of Working Group poll respondents and participants in the half dozen community meetings in which the question was asked this way chose the "some combination" option (of consumers, employers, government, insurance companies, and medical providers; the question did not identify which specific combination people preferred).

In the Sioux Falls meeting, participants were also asked to rate the "degree of involvement" government, medical professionals, insurance companies, employers, and citizens should each have in determining what is included in a basic health care package using the scale: major role, minor role, and no role. Consistent with other findings, 88 percent of participants voted that citizens should have a "major role," and 73 percent indicated that medical professionals should have a "major role." Participants generally believed that government (72 percent) and employers (64 percent) should play a "minor role;" insurance companies received a mixed response, with 55 percent saying they should play a "minor role" and 42 percent saying they should play "no role."

Figure 3 (table):

On a scale of 1 (no input) to 10 (exclusive input), how much

input should each of the following have in deciding what is in a basic

benefit package?

| Location | Federal Government |

State/Local Government |

Medical Professionals |

Insurance Companies |

Employers |

Consumers |

| Jackson | 3.6 |

3.0 |

5.7 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

7.8 |

| Seattle | 4.3 |

4.0 |

5.9 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

7.3 |

| Denver | 4.2 |

4.0 |

6.4 |

2.5 |

3.8 |

6.8 |

| Providence | 4.1 |

3.8 |

6.8 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

8.0 |

| Miami | 5.0 |

4.5 |

5.5 |

2.3 |

3.0 |

6.9 |

| Indianapolis | 4.9 |

3.9 |

6.1 |

2.2 |

3.3 |

7.6 |

| Detroit | 3.5 |

3.7 |

6.8 |

1.4 |

2.4 |

7.6 |

| Phoenix | 3.9 |

3.7 |

5.2 |

2.0 |

3.4 |

7.7 |

| Des Moines | 5.0 |

4.7 |

5.4 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

6.7 |

| Philadelphia | 4.4 |

4.4 |

6.0 |

1.5 |

3.1 |

6.7 |

| Sacramento | 3.8 |

3.8 |

6.4 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

7.4 |

| Billings | 5.1 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

2.4 |

4.0 |

6.3 |

| New York | 5.2 |

4.1 |

6.7 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

7.7 |

| Tucson | 3.9 |

3.4 |

6.2 |

2.6 |

3.2 |

6.6 |

| Salt Lake City | 4.6 |

4.7 |

4.9 |

2.6 |

3.1 |

6.8 |

| Average | 4.4 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

7.2 |

- Participants in some meeting sites discussed a potential

role for a local board or other quasi-governmental entity in defining

the basic level of services. For example, participants in

the Memphis community meeting strongly supported the concept of defining

the basic level of service using a "grass roots" method

through regional or state boards. In these discussions, participants

emphasized the need for a publicly accountable body.

- Participants expressed the desire to be involved in the management of their own health care and were willing to accept some responsibility for their medical decision-making. Meeting participants felt that consumers played an important role in decision-making. This opinion was expressed both by individuals who sought a larger role for government and those who preferred that government have a limited role.

Mental Health Meeting

| At its Boston meeting in August 2005, the Citizens’

Health Care Working Group heard from a panel made up of the Director

of Mental Health Services for Massachusetts, a representative from

a managed behavioral health care plan and an advocate for the mentally

ill. As members of the Working Group attended community meetings,

they heard that access to mental health services was a significant

issue to many participants. In order to delve more deeply into issues

related to mental health, the Working Group sponsored a meeting

focused on this topic in Atlanta, Georgia on May 22, 2006, at Skyland

Trail, a mental health facility which offers long- and short-term

residential care and community-based therapy, with the National

Mental Health Association of Georgia as a host. The participants at this meeting were knowledgeable about mental health. They included providers and consumers of mental health services, family members and advocates for the mentally ill and other health care providers. The meeting format was a mix of questions used at other community meetings and questions specific to mental health. Attendees believed that the value most fundamental to a health care system "that works for all Americans" is universal access, with health care as a right. Other important values are affordability and equal quality of care for all. In considering what was most important to the delivery of mental health care services, universal access was also the most important value, accompanied by integration of mental health into primary health care, parity for mental health care and eliminating the stigma attached to mental health. The issue participants believed most important to address in getting mental health care services is the lack of parity in insurance treatment of mental illness. Other problems that are priorities for action include the need for more funding for mental health services, the stigma associated with mental health conditions, continuity of care and the need for education to help people "know what is wrong and where to go for help." The inappropriate criminalization of mental health behaviors was also identified as a problem. When asked about the delivery of mental health services within the overall health care system, a majority of attendees embraced this vision which was developed by one table of participants: |

A comprehensive delivery system through primary care to include addictive disease, mental illness and all other physical illnesses with: |

|

| Ultimately, attendees wanted a system of "any door" access to services where dollars follow the consumer, and there is a focus on wellness recovery and resiliency. |

How does the American public want health care delivered?

In general, community meeting discussions of how the public wants health care delivered have been structured around two central questions. The first is discussed below:

"What kinds of difficulties have you had in getting access to health care services?"

Individuals at the community meetings discussed a number of problems

they or their family members have had in getting access to health

care services. Some common themes emerged that are summarized below.

| "When you change insurance, you should

be able to keep your doctor." "Primary care doctor—I like that relationship and I don’t want to see that go away." (Charlotte meeting) "It is an accident of history that medical insurance is attached to the place of employment, only to be lost or changed if jobs change or are lost." (Comments submitted to CHCWG Internet "What’s Important to You?") |

-

At the community meetings, individuals asked for a delivery system that is secure, transparent, easy to navigate, and treats the "whole person." Having a continuing relationship with a personal physician is just one component of a stable system, according to the participants. Confidentiality of medical records was mentioned as another important component of a good health care system. Individuals expressed a desire for a system that is holistic, treating the whole person rather than just treating "a bundle of symptoms," as described in the Denver community meeting.

-

Affordability of care is a primary concern among participants. At meetings throughout the country, individuals discussed how costs had prevented them or others from getting needed care. Costs of care generally referred to their (or their family’s) costs, including co-payments, deductibles, and health insurance premiums, rather than system-wide costs. Participants in different cities indicated that the high costs of prescription drugs were a particular concern. Participants in the Salt Lake City meeting discussed how "people are being priced out."

| "More than anything at our table

we have been talking about the cost of the health care –

cost is keeping people from getting the care." (Phoenix meeting) "We want health care delivered equitably at the community level by people we trust." (Memphis meeting) "We have rural areas here in Indiana where you can’t even get a paramedic." "We have lost time-intensive care. Providers right now don’t have time to spend with us! You only get two minutes with your doctor." (Indianapolis meeting) |

National polls have shown that the cost of health care overshadows concerns about quality. In fact, almost three-quarters (73 percent) of those surveyed in a 2005 Gallup Poll said they were greatly concerned about cost; less than half rated other items such as medical errors or avoidable complications, privacy of health information, or availability and access to services as great concerns.5 The EBRI 2004 Health Confidence Survey found that 34 percent of respondents were not at all confident (23 percent) or not too confident (11 percent) in their ability to afford health care today. The figure rose to 44 percent (25 percent not at all confident and 19 percent not too confident) when the respondents were asked about being able to afford care ten years out.6 For the last twenty years, a variety of survey findings consistently showed that approximately one in four Americans reported problems paying medical bills in the previous year.7 Surveys have continued to describe that burden Americans are feeling as it relates to the costs of medical care. According to a 2006 CBS/New York Times Poll, 61 percent of adults said they were concerned a lot about the health care costs they are facing now or will face in the future,8 A Pew Center for the People and the Press Survey found that 54 percent of U.S. adults reported that the costs of paying for a major illness was a major problem and 38 percent said even routine care was a major problem. Moreover, 70 percent of respondents said that the government spends too little on health care, while 65 percent thought that the average American spends too much. 9

| "Culturally competent care-funding

to encourage more minority physicians and providers. If I want

an African American dermatologist, I have to search high and low." (Indianapolis meeting) "You can’t get through this system without luck, a relationship, money, and perseverance." (Salt Lake City Meeting) "Care should be delivered at the most local level possible." (New York Meeting) |

-

Participants were troubled that many people did not have access to the health care they need. Access to care includes access to both facilities and health care providers, including specialists. Participants in community meetings nationwide highlighted problems with access to health care in rural areas, including lack of transportation to providers or facilities located far away. The lack of public transportation was brought up as an issue not only for rural areas, but for urban areas as well. Others described problems finding an accessible provider who was willing to accept their insurance, particularly Medicaid. Providers and facilities tend to be concentrated in suburbs and more populated areas. For example, in the Phoenix community meeting, individuals noted that most providers and specialists were concentrated in the Phoenix area, and it was difficult to access care in other areas of the state. According to a national Wall Street Journal/Harris Interactive survey 56 percent of adults agree that people who are unemployed and poor should be able to get the same amount and quality of medical services as people who have good jobs and are paying substantial taxes. 10

Consolidated Tribal Health Project, Redwood Valley, California

| "I don’t have money to get

my kids milk and you want me to take them to the dentist?" "Society preaches prevention—but a doctor isn’t going to see this young lady’s kids for preventive care. She might get in at a walk-in clinic, but what’s the quality of care? Is the waiting room safe? Is the provider credentialed? Are they culturally sensitive to your needs? We get referred to the outside world where they assume you can read and write and just have you signing forms and don’t take the time to explain it to you." Native Americans (both tribal and non-tribal members) met in Redwood Valley on April 20, 2006, at the Consolidated Tribal Health Project to provide an open, honest, and often emotional insight into the barriers they face in accessing even basic primary medical, mental and dental health care. Participants expressed their desire for everyone to have access to health care, both in terms of geographic distance and ability to access providers. They felt that "health care is not a privilege, it’s a right and we don’t receive that right…not only as Native Americans, but as rural citizens." Individuals addressed the issue of access as a multi-pronged problem. One woman said, "When they can afford to purchase gasoline, their tires are in good shape, and they aren’t in too much pain, they can make the long drive for care." If the primary care reveals a need for specialty services, they face an even greater hurdle. Individuals talked about how they valued culturally competent care with providers who took the time to explain medical terminology and did not assume literacy. One person noted that "[health] professional people are so professional that they don’t know how to relate to us nobodies. They don’t know how to tell us the simple things." Participants at this meeting emphasized the importance of the government recognizing its duty to the Native American population and honoring the trust relationship that is established in law. |

Mississippi Listening Sessions

| Eleven listening sessions organized by faculty

of the Mississippi State University Extension Service were conducted

between March 21, 2006 and April 20, 2006. These sessions were

held across the rural areas of the state and included a diverse

mix of geographies and cultures. Altogether, 138 people participated

in the sessions. The majority of participants were college graduates,

many with post-graduate education, and most had some form of health

coverage. Many of the participants were health care providers

or administrators, or business people actively involved in their

communities, and most were knowledgeable about the problems facing

low-income and underserved rural Mississippi communities. A major

thought expressed across the rural sessions was that many problems

with the health care system in rural areas are distinct from those

found in more urbanized areas. Lack of physicians and other health

care professionals, distances to services, transportation issues,

high cost, and lack of insurance were strongly recurring themes

across the state. Across the sessions, values regarding affordability and quality of care ranked highest among participants. Accessibility ranked third in urgency, but the total number of specific issues related to this concept dominated the discussion. Choice of care rounded out the list of values articulated at the sessions. Those observing the sessions noted that there were marked differences in the views expressed in the meetings, reflecting at least in part, differences in culture, but also the recent major devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina. Participants from the state’s southern regions, hardest hit by the storm, talked about problems they still face getting health care. Doctors left and patient records were destroyed or disappeared. And when some doctors attempt to return, they are finding that their patient base is scattered and possibly gone for good. Concerns were also expressed in the other regions of the state focused on the influx of Katrina and Rita evacuees (many of these evacuees are either uninsured or are covered by Medicaid) and the accessibility barriers that these people faced. Other storm concerns involved the lack of generators for respirators and difficulty accessing medication. One person who became the guardian after the storm of a 3-year old child who is covered by Medicaid seemed overwhelmed: "I don’t know what to do or how to access the system." Another left the same session highly distressed contending that, in light of this system’s inability to quickly respond to Katrina, we had no business focusing on health care issues that will take years to address, and that we should instead focus our attention on the possibility of other natural disasters, a potential pandemic, or a bioterrorist attack. In other sessions, people talked about more pervasive problems, including delays in the ability to schedule an appointment, and physicians who are unwilling to accept Medicaid or Medicare patients. Problems related to communicating with the system led one participant to advocate the establishment of patient navigators. One session in Hattiesburg focused on small businesses’ and independent contractors’ inability to secure reasonable group rates; it was mentioned that 28 percent of National Association of Realtors members have no health care coverage. Most participants (78 percent) agreed with the statement, "It should be public policy that all Americans have affordable health care." Compared to other meetings, however, participants expressed a stronger interest in focusing on personal responsibility (including taking advantage of educational opportunities) to improve health care and control health care costs, investing in public health infrastructure, and expanding safety net programs in order to ensure access to care. There was also a greater emphasis on expanding existing public programs and bolstering the employer-based health care system to address gaps in coverage, rather than initiating new programs or making fundamental changes to the health care system. The most resounding dialogue the group facilitators recalled at all the sessions focused on the availability of health care services. |

-

Many participants cited complexity of the system as a contributing factor to the problems with the health care system. A number of issues related to complexity were discussed. Some participants noted that a lack of transparency in insurance coverage and reimbursement policies contributed to the problems. In the Memphis community meeting, the discussion of the complexity of the insurance system emphasized the problems created by multiple payers. Related to the concept of multiple payers, participants in the Denver community meeting discussed how the "labyrinthine scheme of Medicare and Medicaid" sets up a system especially hard to navigate by or on behalf of elderly patients. In the Providence, Philadelphia, and Sacramento community meetings, the new Medicare prescription drug benefit (Part D) was cited as an example of the complexity of the health care system.

| "It’s so complex. You wake up one day and your contract has been renegotiated, your numbers have changed, and your providers have changed. There are too many rules and too much bureaucracy." |

- Linked to confusion about the health care system was the

lack of useful information to help individuals navigate the health

care system. Individuals wanted to have access to understandable

medical information to help them make educated decisions about their

health care. Many participants discussed their desire to partner with

their health care provider in making health care decisions. Participants

noted that sometimes it was very hard to find any information, although

we also heard from some participants that information was available

if one knew where to look. People often were not sure where to go

to find what they needed. The desire for information is not unique

to Working Group community meeting participants. According to a 2005

Gallup Poll, a slim majority (51 percent) of individuals said they

do not have enough information about hospitals and other health care

facilities to make educated choices for health care services. 11

- Participants mentioned that they or others were not always treated with respect or dignity. Examples of problems people encountered included a lack of effective communication, discrimination by race or ethnicity, long wait times, and overcrowded emergency rooms. In a number of locations, meeting participants discussed how they had encountered or knew of barriers due to race or ethnicity, language, lack of cultural sensitivity, and lack of health insurance.

| "It’s often more stressful to

deal with the insurance company than it is to deal with the disease."

(Des Moines meeting) "There should be no waiting period before becoming eligible for coverage." (Lexington meeting) |

- Participants frequently cited barriers to care related to their insurance coverage. People in community meetings mentioned that they have experienced problems getting care due to health insurance rules. For example, some services were not covered due to pre-existing conditions. Participants also discussed problems related to needing to go through an insurer’s gatekeeping requirements to receive referrals that sometimes were denied. A number of participants spoke of problems with the portability of health insurance under the current system. Within the employer-based health insurance system, someone who changes jobs might be forced to switch insurance and could lose access to their health care provider if that provider is not in the new network. Participants in the Billings community meeting noted that limited provider networks created access problems in Montana, a large but lightly populated state. In the Baton Rouge community meeting, participants noted that the experience from the hurricanes in the summer of 2005 brought to the forefront the need for major emergency preparedness in all aspects of the health care system, including among insurance providers.

The second question asked of community meeting participants about health care delivery relates to their priorities for getting needed care:

"In getting health care (choosing a physician, health

care provider, or health plan), what’s most important to you?"

The responses to this question built on the answers to the previous question about problems getting care. The primary themes related to affordability, accessibility, and forming mutually respectful relationships with providers.

- Participants told the Working Group that they want to feel secure knowing that when they or their families need care, they can get it without becoming impoverished. Discussants frequently mentioned that it was important that their out-of-pocket costs for health care not be unreasonably high. Participants said people should have to pay some amount, but they generally also said that patients of all income levels should be able to receive needed care without costs being a barrier.

| "I feel like we are only as good as

our weakest link, and so many people can’t afford care." (Fargo meeting) |

- Participants wanted all Americans to be able to get the

right health care, at the right time, in a respectful manner. Access

for everyone emerged as a common theme across meeting sites. Some

meeting participants said that receiving "the right health care"

meant that medical decisions would not be based on factors such as

a person’s age. Many participants decried making medical decisions

on the basis of cost rather than medical need, but did want the care

they receive to be delivered in a cost-effective manner. Participants

expressed the need to have care received in a coordinated and timely

manner. Among other factors, getting the right care in a respectful

manner involved having a provider who was courteous and could communicate

well. As stated in meetings from Charlotte to Seattle, participants

believed that care should be sensitive to the needs of different cultures.

The desire to be treated with respect has also been shown to be highly

valued in other national surveys. A 2004 Wall Street Journal/Harris

Interactive poll asked what qualities people believed were extremely

important from the doctors who treat them; some of the most popular

responses related to the medical provider’s interpersonal skills—such

as being respectful (85 percent) and listening carefully to health

care concerns and questions (84 percent). 12

- Participants noted that being able to choose and maintain a stable, long-term relationship with a personal health care provider was critical. Individuals at meetings throughout the nation reiterated the importance of the provider-patient relationship that they believed should not be affected by whether a person switches jobs or changes health insurance. In the Phoenix community meeting, participants valued being able to choose a provider that would listen to them and provide "true" care, rather than just writing out a prescription. They wanted to be able to keep their health care provider even if they changed insurance carrier. In a number of locations (such as at the meetings in Orlando and Detroit), participants also discussed the importance of choosing a specialist. Participants at the community meetings told the Working Group that they placed a high value on having a "medical home" in which they can spend individual time with a provider. On the other hand, some participants at other meetings, such as San Antonio, expressed a willingness to forego some choice of primary care physician in exchange for lower costs or higher quality care.

How should health care coverage be financed?

Community meetings tended to devote a substantial amount of time to questions related to financing health care and controlling health care costs. The first of five questions that were commonly used in community meetings asks participants their opinion on whether everyone should be required to enroll in basic health care coverage:

"Should everyone be required to enroll in basic health care coverage, either private or public?"

Meeting participants had interesting discussions in response to this question:

-