The Health Report to the American People

See this document in print-ready PDF format.

Last modified: September 29, 2006.

Contents of the Health Report

Contents of the Health Report

I. A Snapshot of Health Care Issues in America

Health care is getting more expensive - and costs keep going up.

Quality of care falls short of the mark.

Many Americans don't have access to health care services.

These problems work together to cause serious consequences for our society.

II. Health Isn't Guaranteed-We Are All at Risk

III: Sharply Rising Costs

We're spending hundreds of billions of dollars on health care - and the numbers keep going up.

IV. Quality Shortcomings

V. Access Problems: Not Getting the Health Care You Need

Sudden changes can eliminate coverage.

VI. What is Being Done?

I. A Snapshot of Health Care Issues in America

Every American needs health care services - for routine check-ups and preventive care (such as flu shots), for treating chronic conditions like diabetes, for receiving urgent care for serious injuries or illnesses, and for helping us live comfortably in our last days of life. Our need for health care varies over the course of our lives and can change based on our situation at a given time. We are all at risk for needing critical and expensive care.

How well our health care system responds to our needs for care and the costs associated with delivery of this care are subjects of much debate. There is clear evidence that rising health care costs, unreliable quality, and lack of access to needed services are key problems which must be addressed as we work to develop a health care system that works for all Americans.

Health care is getting more expensive-and costs keep going up.

- Costs are rising sharply - Our costs for health care were estimated to be about $6,300 per person in 2004 [12], and are projected to increase to about $12,300 by 2015 [19].

- We spend more now than we did in the past - In 1960, we spent about a nickel out of every dollar on health care in the United States. Today, our spending has tripled to about 15 cents out of every dollar, and that proportion is expected to rise sharply over the next ten years [11].

- We’re making fundamental choices in our own lives based on the costs of health care - The need for employer-sponsored health insurance to cover the high costs of medical care is why some workers postpone retirement, why some mothers re-enter the workplace, and why some people decide against starting their own small businesses.

Quality of care falls short of the mark.

Many of us are benefiting from medical advances, and are living longer, healthier, and more productive lives. However, medical care is complicated and medical science cannot always provide solutions to all our health problems all the time. In addition, our health care system is very complex and has many layers, including doctors, insurance companies, and hospitals. The red tape and communication barriers inherent in the system can create hurdles for both health care providers and for patients. Many of us receive inappropriate or unnecessary care:

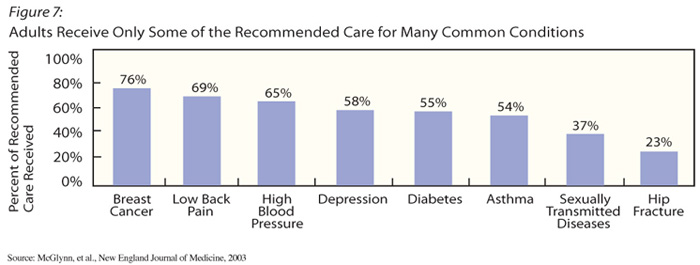

- Adults get, on average, only 55% of the recommended care for many common conditions [2].

- Many unnecessary medical errors occur. From 44,000 to 98,000 deaths are estimated to occur annually due to medical errors [5].

Americans often face difficult decisions, such as end-of-life care:

- Not all of the care people receive at the end of life is effective in improving quality of, or prolonging, life.

- We're spending about a quarter of all health care costs on caring for people in their last year of life [7].

- More than half of Americans say that being able to be at home when dying is important, but only 15 percent of Americans die at home [8].

- 93 percent of those asked believe that being free of pain is important, but only 30 to 50 percent of Americans achieve this objective [8].

Many Americans don't have access to health care services.

Even though our country has pioneered many major medical developments, millions of Americans do not have access to needed medical care. Some areas of the country do not have enough or the right types of health care providers to serve the population’s needs. And more than 15 percent of Americans report that they have no regular place to go when they need health care [6].

Compounding the problem is that many people lack insurance coverage to pay for the health care they need. Some individuals have no coverage at all; others have limited coverage that may not include some important services or may require high out-of-pocket payments before coverage kicks in. People may also have inadequate coverage for specific services such as prescription drugs, mental health or long-term care. For example, no more than 10 percent of elderly people have private insurance for long-term care [118].

Generally, there are two main sources for funding for health insurance in America. Private funds consist of payments for health insurance premiums and payments that we make directly out of our own pockets when we get care. Most private coverage is purchased by employers on behalf of their employees. Public sources of funding use tax dollars to fund federal, state, and local government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, some people rely on programs that combine public and private dollars.

However:

- Over 46 million Americans have no health insurance,1 [52] and many more have insurance with limited benefits.

- Most of these uninsured people are in working families, and most are in families with incomes above the poverty line. Many people either can’t afford to buy health insurance or choose not to buy it [9].

- Uninsured Americans are nearly eight times more likely than Americans with private health insurance to skip health care because they cannot afford it [10]. These Americans may face serious health consequences from delaying or failing to get timely and effective health care when it's needed.

- A person’s race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status continue to be associated with differences in the quality of care provided, the person’s access to care, and the person's overall health.

These problems work together to cause serious consequences for our society.

Our health care system is threatened by rising costs, unreliable quality, and problems accessing care. These problems are complex and interrelated, because the entire health system works like an “ecosystem,” where changes made in one aspect of the health care system can affect other parts of the system. New technologies can improve the quality of care, but may lead to even higher costs. Rising costs contribute to increasingly unaffordable care. And when people without health insurance or with inadequate benefits receive care they can’t pay for, costs for others can increase.

Together, all of these problems affect many aspects of our society:

- Individuals – Americans are having increasing difficulty protecting themselves against catastrophic loss and are having trouble paying for the increasing costs for health care.

- Government – Increased costs are placing pressure on our government’s ability to pay for other programs. This may create a need for tax increases, cuts in health care benefits, or cuts in other public programs.

- Businesses – Higher health insurance premiums make businesses less likely to offer comprehensive health insurance to their employees. Higher premiums also make it harder to afford insurance. If current trends continue, employers and their workers could experience decreasing profits and wages because of the rising costs of health care. Jobs are also being outsourced to other countries as businesses strive to save money.

Exploring options.

States, communities, and large health care systems are attempting to deal with the interrelated health system issues of cost, quality, and access. In hearings around the country, we heard about several interesting public and private sector initiatives that have been put in place. Designing and implementing these programs requires substantial financial and institutional support. Sustaining the efforts presents new challenges. Most of these programs are new, so we don’t know yet how well they will work over the long-term. And, because these programs were designed to work in particular places, we don’t know whether the programs would fit, or work successfully, in other locations or settings.

Other programs we learned about are more narrowly focused: some are designed specifically to control health care costs; others focus on improving the cost effectiveness and quality of health care; still others concentrate on improving access to primary care services or expanding health insurance coverage to a greater number of people. Still other approaches are aimed at improving efficiency by offering rewards to providers for delivering cost-efficient, high-quality services, such as providing recommended health screenings, or when a high proportion of their patients receive appropriate care for conditions such as diabetes or heart disease.

Over time, more efficient ways of operating health care organizations and using health information, as well as general improvements in our health, could ease some of the pressure on our health care system. While investments now could reap important rewards over time, the benefits from these broader improvements will not eliminate the growing, interrelated problems that face our health care system.

Our review of the evidence reinforces our conclusion that we need to address the entire health care system, not just specific problems in cost, quality, or access, no matter how urgent they may seem from our different perspectives. Ideally, savings gained from improving efficiency and quality in the system can be used to make other needed changes. But no single initiative that we have reviewed can provide all the answers to our health care system’s problems. That’s why we need to engage you in this discussion.

II. Health Isn't Guaranteed-We Are All at Risk

“I was an elementary science teacher. I ate right, exercised regularly, and was rarely ill. I had only fleeting contact with the health care system. But then I got sick. I was always tired no matter how much sleep I got. My vision became blurry, and I had difficulty hearing sometimes. Eventually I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a chronic neurological disease.”

– Montye Conlan

As Montye’s story shows, you never know when you’ll need to take advantage of health care services.

Normally, people’s use of health care services consists of routine medical and dental checkups, none of which are overwhelmingly cost prohibitive for most Americans. But we tend to be affected by more health care problems as we age. As individuals in the Baby Boom generation age, the demands on the health care system will increase substantially. If medical science continues to advance, people will also live longer and will require additional health services.

Services we all need.

Some of our health care is provided in hospitals, some is provided in physician offices, and some is provided at home, in a rehabilitation facility or in a nursing home. We pay for many medical and surgical procedures and prescription drugs that are very expensive, but we also use a lot of low-priced services and drugs.

From routine care to treating serious

injuries or illnesses, Americans need health care:

|

We spent $1.9 trillion in 2004 on health care, much of it falling into the following categories [122]:

- Professional health care services. These services, such as those provided by physicians, nurses, and dentists, accounted for about $587 billion in 2004. This is almost one-third of all the money we spent on health care services and supplies [122]. Although most routine doctor and dental visits are not very expensive, we make many such visits.

Last year:

|

- Hospital services. Hospital care remains the second most expensive type of health care. Hospital costs amounted to $571 billion in 2004 [122], even though only 7 percent of Americans spent the night at a hospital [20]. While most of us do not need to go to the hospital in any given year, it is usually very costly when we do, and sometimes extraordinarily so. In fact, the average cost of a hospital stay in 2002 was nearly $12,000 [21].

- Prescription drugs. The amount we spend on prescription drugs ranked third compared to our spending on other health care services in 2004 [122]. We are spending more of our health care dollar on prescription drugs than we ever have in the past. Not only are we buying more drugs than before, but also we are spending on newer drugs that cost more [24]. The rapid increase in brand name prescription drug prices has also contributed to our high spending.

Prescription drug use – and spending – continues

to increase rapidly:

|

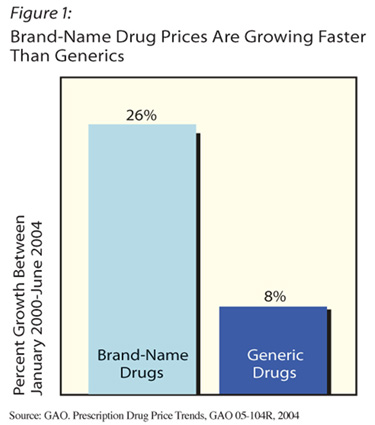

Some popular prescription medications are now available in generic form(chemical copies), which has lowered their cost [25]. As shown in Figure 1, prices for brand-name drugs grew three times as fast as prices for generic drugs.

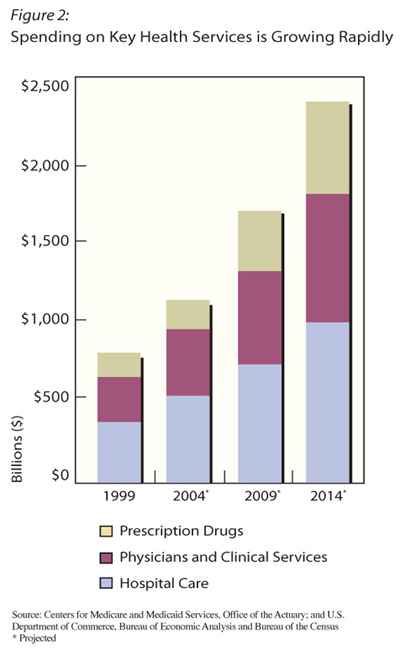

As shown in Figure 2, national spending for the top three health care services (hospital care, physicians and clinical services, and prescription drugs) is expected to increase rapidly over the next decade.

- Long-term care. More people today have disabilities or chronic care needs that require long-term care through a range of medical and social services. They generally have serious problems performing basic activities such as bathing or dressing. The services they need may be provided in their homes, in adult day care facilities, in nursing homes or assisted living facilities [26].

Nursing home and home health care costs are increasing significantly as a share of what we spend on health care. This is a result of the fact that the American population is living longer. Expenditures on nursing home care and medical equipment are rarely covered completely by public or private insurance. Americans paid out-of-pocket for a considerable portion (about 28 percent) of nursing home care in 2004 (almost $32 billion) [12]. Americans also paid out-of-pocket for a wide variety of medical equipment and other medical supplies, totaling just over $40 billion. [122]

Nursing home and home health care costs are increasing:

|

Different people, different needs.

As Montye Conlan’s story at the beginning of this section shows, Americans are always at risk of needing various health care services, often when least expected. While our need for services can be unpredictable, a number of factors do influence both what kind of care people need and the costs they incur for these services. A large portion of all health care is used by a small number of people. Private insurers and public programs try to spread these costs to make it possible for everyone to get care when they need it.

Age

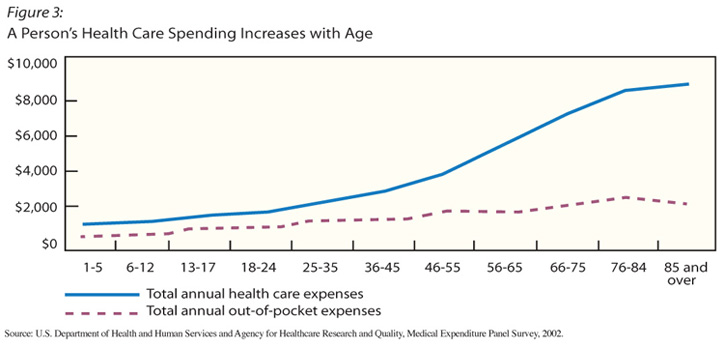

Health care expenses are relatively low during childhood. In fact, only one-fifth of all lifetime health care expenses occur during the first half of life [29]. As we age, however, our health care needs increase, especially between ages 65 and 85:

- About half of all health care expenses in a person’s lifetime occur after age 65 [29].

- Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older are more than twice as likely to use hospital services as are younger adults [25].

- The annual average expense for the care of adults ages 76 to 84 is $8,000 – nearly eight times the average health care costs for children ages 1 to 5 years [21]. (See Figure 3.)

| People need different types of health care according to

how old they are and which health problems they have.

Ages 0 - 5

|

Serious and chronic conditions

Regardless of age, any of us can experience illnesses or injuries that require serious medical attention at any time. These ailments cost significantly more than routine care. In any given year, close to half of all health care spending pays for the care received by only 5 percent of the population – those experiencing serious health care conditions [30]. Some of those conditions last only a short period of time, while others are chronic, or ongoing.

In 2004, almost half of all people in the United States had a chronic condition that ranged from mild to severe. That year, 23 million Americans had heart disease, 22 million had asthma, more than 13 million had diabetes [22], 400,000 had multiple sclerosis [31], and more than 750,000 had cerebral palsy [32].

The ten most costly chronic

conditions for adult Americans are:

|

More than 39 million adults have two or more chronic conditions. Managing chronic conditions can require people to change their lifestyles or even their jobs. Serious chronic illness may require a lot of health care and expensive medications over long periods of time. Health care for people with chronic diseases accounts for 75 percent of the nation’s total health care costs [34]. For example, people with diabetes incurred an average of $13,243 in health care bills in 2002 [35].

Alternatively, certain illnesses or injuries also require extensive medical care, but only over a short time period. These costs can be equally prohibitive:

- In 2001, the insurance costs for a premature baby (defined as being born more than 2 weeks early) averaged over $41,000 for the first year – almost 15 times as much as for a full-term baby ($2,800) [36]. The hospital costs for the one in one-hundred newborns with the most serious health problems average over $400,000 [37].

- The average cost for surgically repairing a torn knee ligament is

approximately $11,500 [38].

Other factors

Lifestyle factors such as exercise, diet, and environmental and living conditions can affect Americans’ health needs. Research suggests that race and ethnicity, attitudes about going to a health care provider, and the ability to understand health care and how to use it, are also significant factors in determining how people seek as well as receive health care [39, 40].

In addition, as we discuss in other sections of this report, the amount and type of health care services that Americans use reflects how much people believe they can afford, as well as the availability of doctors, clinics, or hospitals.

III: Sharply Rising Costs

“My husband had some complications with his back surgery and wound up on a respirator in the intensive care unit for five days, in a neuro-acute unit for four more days. Even though he and I both had insurance, the 20 percent [coinsurance] of the bill was $80,000.”

– Chris Wright

Americans are fortunate to have medical technologies in this country that can save lives. You never know when an unexpected illness or injury might mean that you, too, need to rely on new, cutting-edge services. But at the same time, top-notch care comes at a high cost, as Chris found.

In one way or another, whether through taxes, higher prices, or lower wages, the American people—about 290 million of us [42]—supply all of the money used to pay for health care. To have a constructive discussion about what changes should be made to improve our health care system, we need to understand more fully the flow of dollars in the current system and why health care costs are continuing to rise rapidly.

As you review the information in this section, keep in mind that this story is only partly about dollars. Health care is personal. Over our lifetimes, all of us will interact with the health care system as patients, relatives or friends of patients, and caregivers. We all have a stake in preserving what works in the system, as well as fixing what does not work.

We're spending hundreds of billions of dollars on health care - and the numbers keep going up.

The amount this country spends on health care is extremely large:

- In 2004, we spent about $1.9 trillion dollars on health care services, medical research, and other things related to health care, like running and building hospitals, clinics, and laboratories [122].

- Almost all of that money – 93 percent – was spent on health care services and supplies.

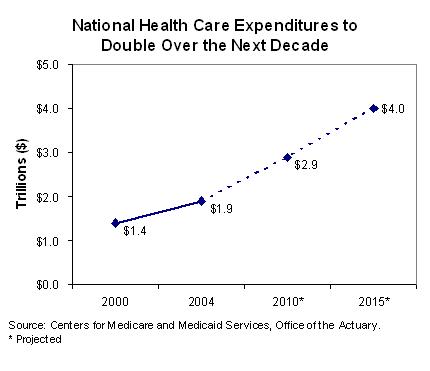

- Our spending for health care was, on average, about $6,300 per person in 2004, and this spending is projected to increase to $12,300 per person by 2015 [19].

- Overall health care spending is predicted to be $4.0 trillion in 2015. (See Figure 4.)

We spend much more on health care than what the official numbers show. Informal care-giving—care provided by family, friends, and volunteers, often at no charge—does not show up in the spending estimates:

|

Americans are spending more on health care than ever before:

- In 1960, we spent about a nickel of every dollar of income on health care. In 2001, we spent nearly triple that amount, spending 14 cents of every dollar on health care [11].

- By comparison, our spending on education has not grown nearly as

much. In 1960, we spent about a nickel out of every dollar on education

at all levels—primary, secondary, college, and university. Forty-one

years later, we had only increased our education spending to seven

cents out of every dollar [11].

And every year, an even larger portion of our federal dollar goes to health care:

- The growth in the resources Americans now put toward health care is greater than the growth in resources for many other kinds of goods and services we need and use.

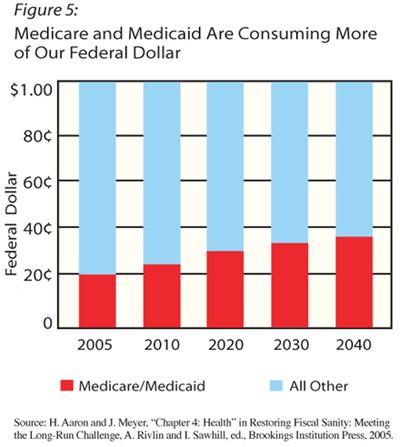

- If trends continue to follow the path of the last 20 years, Medicare and Medicaid will account for nearly 30 percent of all government spending by 2020, and about 36 percent by 2040[45]. (See Figure 5.)

We all pay for health care.

We are paying our growing health care bill through sales, income, property or payroll taxes, or through increased premium payments, reduced wages, or when we pay higher prices for the products and services we buy. That money is channeled through private and public sources, including what we pay out-of-pocket, to health care providers.

Private funding for health care.

Private spending consists of what people pay for health care, indirectly through their premiums to insurers or directly through out-of-pocket payments to providers, as well as contributions made by charities and other private organizations.

Private health insurance’s largest single expense – 39 percent of its total spending – was for professional services provided outside of a hospital, such as doctors’ visits [37]. Although private insurance typically offers some coverage, more than a third of what people with private insurance spend out of pocket for health care pays for these services – mostly doctor visits and other clinical care ($38 billion) and dental services ($33 billion). People with private insurance also spent a lot on prescription drugs. In 2003, they spent nearly $53 billion out-of-pocket for prescription drugs.

Most private coverage is purchased in the group market by employers on behalf of their employees. In 2005, virtually all large companies offered health insurance to their employees. Only half of the smallest companies (fewer than 10 employees) offered it. Increasingly, firms are requiring employees to make contributions toward the premiums, for both single and family coverage. In 2005, the typical employee paid over 15 percent of the premium for single coverage and almost 30 percent of the premium for family coverage, averaging $610 a year for single coverage and $2,713 a year for family coverage [46].

Employer health coverage is subsidized through the federal tax system, since workers do not have to pay taxes on compensation received in the form of employer-provided health insurance. Premiums paid by employers that are part of employees’ compensation are exempt from payroll taxes and from individual income taxes. As a result, both employers and employees pay less in taxes than they would if employees were paid only in wages, and, for many employees, there is an effective discount on their premiums because group rates (through employers) are generally lower than premiums for individual coverage. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that, in 2004 alone, the exclusion of health benefits from taxation will reduce federal revenues by $145 billion [47].

The private sector also plays a critically important role in supporting health research in the United States. Industry—pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device firms— pays for more than half (57 percent) of all the biomedical research conducted here, adding up to close to about $54 billion in 2003. Other private funds, mostly foundations and charities, pay for another 3 percent. Industry support for the development of pharmaceuticals, biomedical products, and devices has grown rapidly, more than doubling from 1994 to 2003 (after adjusting for inflation). Spending on research on medical devices has been growing particularly fast, increasing by 264 percent from 1994-2003 [114].

Public programs

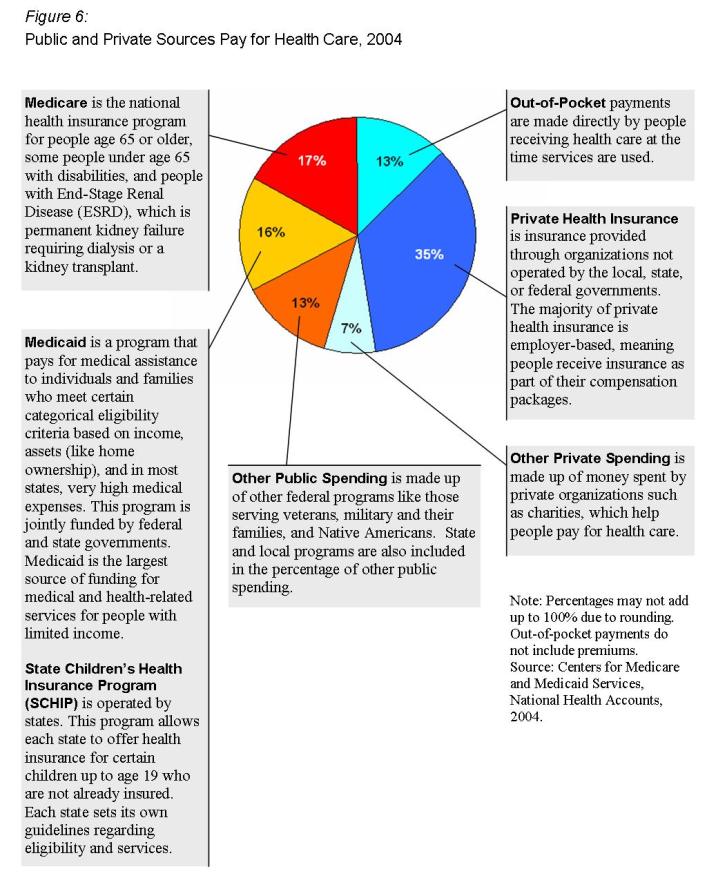

Federal, state, and local governments support a variety of public health care programs. The two largest government programs are Medicare and Medicaid. These programs make up about a third of our total national health spending (see Figure 6). The way these programs work affects virtually every aspect of our health care system. Throughout this report, we talk about ways that Medicare and Medicaid are trying to address many of the problems facing our health care system, including innovations to improve quality of care and increasing access to health insurance.

Medicare is a national health insurance that covers almost everyone in America age 65 and over as well as millions of people under 65 who have become disabled or have developed end-stage kidney disease. In 2004, Medicare covered about 35 million seniors, over 6 million persons with disabilities, and 100,000 people with end-stage kidney disease [48]. About half of the money collected for Medicare comes from a specific payroll tax that goes only into a special Medicare fund, and almost a third comes from general revenues from income and other federal taxes. Individuals covered by Medicare also pay premiums, which are taken out of their Social Security checks each month. In 2006, individuals with Medicare coverage of physician and other health care services pay $88.50 per month in premiums ($1,062 per year), plus, if they chose to enroll, an additional premium (estimated to average $25 per month) for the new Medicare prescription drug benefit. [123]

The federal government also uses general income taxes to pay for a large portion of the Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) programs. Medicaid is a national program run by the states that provides medical assistance to certain low income individuals and families (eligibility varies by state). In 2004, about 55 million people were enrolled in Medicaid at some point during the year, and almost half of them were children [50]. About 6 million children were enrolled at some point in SCHIP in 2004 [51]. State governments also use tax money to help pay for Medicaid and SCHIP.

Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP cover different types of services for different populations. However, all are facing increasing costs.

- Medicare’s spending on hospital care is projected to almost double over the next 10 years – from $163 billion in 2004 [122] to about $340 billion in 2015. More than half of Medicare’s spending goes to pay for hospital care – which is often very expensive – for its growing population. By comparison, around a third of either Medicaid’s or private insurers’ spending goes to hospital care [122, 12].

- Medicare’s spending on physician and clinical services is also projected to more than double by 2015 [12].

- Medicare’s share of prescription drug expenses will increase dramatically in 2006, when Medicare Part D coverage of prescription drugs first takes effect.

- Medicaid pays for more long-term care than any other public payer or private insurer. As a result, a significant portion (about 20 percent) of its expenditures for health services and supplies are spent for nursing home and home health services [12]. The number of people age 65 and older who will use a nursing home during their lives is expected to double over the next 20 years, and one-quarter of those entering a nursing home are expected to be there for at least one year [28].

- From 1993 through 2003, Medicaid payments for long-term care such as personal care services, adult day care, transportation, or skilled nursing services more than doubled, growing by more than $62 billion [27].

- Both Medicaid and SCHIP are covering a growing number of people,

primarily poor children whose families cannot afford health coverage

[52].

Public funds also pay for other important health care programs, including the health care provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense programs for the military (and their dependents and retirees), and the Indian Health Service. In addition, federal money is used for public health activities such as infectious disease control and bioterrorism preparedness through agencies like the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both state and local governments use tax revenues to pay for other health care services, such as local clinics, public hospitals, and prescription drug assistance.

All levels of government support medical research, education, and training of health care professionals. These kinds of programs do not provide services directly but still play an essential role in health care.

Biomedical research plays a particularly important role in shaping health care in America. This research is essential to development of medical advances and technological breakthroughs that improve the effectiveness and quality of medical care and thereby prolong and enhance the quality of our lives. [114]

In 2004, the Federal government spent over $33 billion on biomedical research, mostly at the National Institutes of Health. While private industry is the largest direct source of funding for biomedical research, the federal investment is critically important. The NIH budget doubled in the five years from fiscal year 1999 though 2003. The agency provided more than $15 billion in project grants to researchers, and several billion dollars more in grants to research centers around the country [119]. In addition to providing funding to researchers in universities and in industry, the federal government also builds research programs in the private sector by providing “seed money” that can increase the chances that private sector organizations will add their support to new research initiatives [120]. There is also some federal investment in research to calculate the clinical and economic value of new and existing medical treatments and technologies. In fiscal year 2005, the federal government spent about $1.8 billion on all types of health services and health policy research combined [121].

Numerous factors contribute to rising costs.

A combination of factors, including how we use technology and how much we pay for health care contribute to rising costs. The prices we pay are affected by the way the health care system is organized in the United States.

Technology

America leads the world in medical technology research and development. Total spending on biomedical research has been increasing rapidly, growing from $37 billion in 1994 to about $94 billion in 2003. Investments in research have made the United States the global leader in pharmaceutical development: by one estimate, about 70 percent of all new drugs under development around the world in 2003 belonged to organizations headquartered in the United States. This level of achievement has important benefits, both for our economy and for our health care [114].

There is no question that the products of this research, such as vaccines, and other drugs, and devices used in the diagnosis and treatment of disease, save countless lives. Our current health care system lacks effective mechanisms for weighing the relative benefits of new health technology. However, is it appropriate to limit this research because these new potentially life-saving products are, in part, responsible for driving up health care costs?

The way that we use technology — using many, often expensive, tests, using sophisticated equipment and expensive new treatments— has been suggested as a major cause of the country’s large increases in health care costs [53]. For example, Medicare increased its spending for imaging services, such as magnetic resonance imaging services (MRIs), in physician offices alone by over $3 billion from 1999 to 2003 [54]. While it is difficult to weigh the costs and the benefits of life-enhancing technologies, the decision to use them is often made without patients, families, or those receiving or paying for the care fully understanding the possible benefits and problems that may result [91].

The way we pay for care

In our fragmented health care system, there are many ways in which we pay providers. Some ways we pay for health care in the U.S. may lead health care providers to provide more, rather than fewer, services. For example, in fee-for-service systems, physicians and hospitals are paid each time they provide a service; the more they do for patients, the more they get paid. At the same time, how much patients have to pay when they use health care services may affect their decisions about getting care.

The actual prices we pay for medical services and supplies are also affected by how much it costs to run health care organizations. For example, physicians and other professional health care workers’ salaries are higher than those in other industrialized countries [56]. Other factors, some of which are discussed below, may also drive prices. Whatever the reasons, prices we pay for health care tend to be high. The approaches we have tried to control health care costs have not proved to be very effective. For example, managed care, which pays providers a fixed amount for each patient, gave doctors a strong incentive to use services carefully. While managed care seemed to reduce health care cost increases for a short time in the 1990’s, health care costs accelerated again in part due to public backlash against managed care’s limits on access to services [112]. We have relied on competition among providers in the private sector to determine what prices are and have generally not wanted to have the government directly control prices as some other nations have.

Administrative costs

We pay for health care in a very complicated way: different government agencies, insurance companies, and individuals all pay for part of various health care bills. This complex system can lead to duplications and inefficiencies, which result in higher administrative costs. Patients also suffer, wasting time and undergoing numerous frustrations as paperwork costs are passed on to them.

Hospitals and doctors’ offices in the United States often employ many workers to process bills and payments, since the bills go to several different government programs and various private insurance companies. In contrast, fewer employees are needed for this purpose in systems where there are fewer payers, such as the health care systems in many other industrialized nations, because there are fewer payers for health care [3]. The health services industry is the largest industry group in terms of employment in the United States [55].

In our multiple payer system, some administrative costs are necessary for organizations to run smoothly. Your family doctor, for example, must not only pay for staff to process bills, medical records and other paperwork, but also to coordinate your care with other health care providers. Your employer, likewise, pays for staff to manage the company’s health insurance plan and deal with changes in enrollment, billing problems, and so forth. Some activities that fall into the category of “administration” may add value to health services. Employers may sponsor prevention and wellness programs designed to increase the effectiveness or efficiency of health care in various ways. Insurance carriers and health plans spend part of their budgets on developing and marketing new products. These are part of the costs of doing business in a competitive market.

There is no agreement on what exactly administrative costs are or should be, and estimates of how much is spent on them vary considerably [57]. For example, the administrative costs for 232 Medicare managed care plans ranged from 3 percent to 32 percent of total costs in 1999, according to the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services [58]. Administrative costs for the Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) were 14 percent of the agency’s FY 2005 budget [59]. Another insight about administrative costs can be found in the formula that the Medicare program uses to pay physicians. It uses an estimate of physicians’ medical practice expenses, which include employee wages, office rent, and supplies and equipment [60], as well as the costs of professional liability insurance, to set payment rates. Together, practice expenses and liability insurance account for about 48 percent of Medicare’s annual payments to physicians [61].

About 8 percent of total national health spending in 2004 went toward administrative costs and profits of insurance companies, plus the costs of running government programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. This does not include the administrative costs of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers [122]. Private insurers may pay about three times more in administrative costs than Medicare [62]. However, private insurers may use some of this money to provide programs like disease management or consumer education programs that government insurance does not offer. Some experts believe, in fact, that government programs may not spend enough on administration; greater investment in administration might help public programs such as Medicare be more efficient and provide better service, reduce errors, or identify fraud and waste [63].

Waste, fraud and abuse

One approach to reducing spending is to try to eliminate waste. Sometimes we get more care than we need because we, or our doctors, are not sure what is best, and we would rather err on the side of caution (issues related to overuse of care are discussed under Quality Shortcomings). But it is also important to consider whether a less expensive type of medical test can be substituted for a costly one without causing harm, or whether the price of certain services is unnecessarily high.

Preliminary estimates for 2005 show that the Office of Inspector General’s efforts to reduce waste in government health programs will recover $15.6 billion of fiscal year 2005. In addition, audits to uncover fraud and abuse are expected to recover an additional $1.4 billion [66].

We all feel the burden.

Increasing health care costs affect every aspect of our economy, from the individual level to all levels of business and government.

Individuals

Across America, people are feeling the effects of rising health care costs in different ways:

- Problems paying for any care at all – Some people simply can’t afford to pay for health care. Hospitals, clinics, doctors, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists are seeing an increasing number of people who seek care but are unable to pay for it [67]. People may also have to cut corners by doing without the prescription drugs, physical therapy, or medical supplies they need. If employees have to pay more for their health insurance coverage through their employers, many low-income workers may turn down this coverage and instead go without insurance, joining the ranks of the uninsured [70]. As discussed earlier in this report, people without insurance may postpone preventive care. They may gamble on not getting sick or being injured in accidents that might require expensive medical care. When they do need and receive care that they are unable to pay for, everyone from health care providers and taxpayers to people with insurance shoulder the costs.

- Obstacles to getting the care they need – As health care providers spend more on medical equipment, supplies, and personnel (including the costs of providing health insurance to health care workers), some reduce costs by providing less charity care to people who can’t pay [67]. Even if they do serve these patients, it may become increasingly difficult to obtain referral and specialty services, equipment, and prescription drugs for uninsured patients; some people may not be able to get the care they need [68].

- Pressures on household finances – As a whole, Americans spent two months’ worth of their earnings on health care in 2003. In another 10 years, health care spending could eat up another week’s earnings, leaving less money for housing, food, and transportation.

Health care providers

Even with governmental support and private insurance, many providers are still left with unpaid bills. In 2001, it was estimated that people who were uninsured or were unable to pay the full costs of their care used about $35 billion in services that neither private nor public insurers paid for [69]. Part of the cost is reimbursed by public programs, but much is passed, or “shifted,” to consumers through higher costs for services or higher insurance premiums.

Businesses

Employers are finding it increasingly difficult to carry the burden of offering insurance to their workers and their dependents. As a result, they may:

- Experience decreasing profits and offer fewer wage increases.

- Raise the prices of the goods and services they offer, increasing costs for consumers.

- Ask their workers to pay a higher dollar amount of rising health insurance premiums.

- Shift jobs overseas to decrease their labor costs.

Government

If health care spending continues at its current pace, our national debt could continue to increase:

- Currently, 19.6 percent of all federal spending goes toward the two largest federal health care programs, Medicare and Medicaid. State governments are also feeling the pressure of soaring health care costs [45].

- If health care costs continue to grow as they have, all of the growth in the economy will go toward health care by 2051 [45], leaving no resources for expansions in other areas.

Underlying these trends is the coming impact of the Baby Boom generation. When the Boomers – people born just after World War II – reach age 65 (starting in 2011), the number of people enrolled in Medicare will double [48]. As discussed in Section II of this report, people between ages 65 and 85 need more health care services and incur more health care-related expenses.

IV. Quality Shortcomings

Our care doesn't always meet medical standards.

Most Americans are generally healthy and satisfied with their care. In 2002-2003, 85 percent of Americans reported being in “excellent”, “very good” or “good” health [71], and about half of Americans say they are “very” or “extremely” satisfied with the health care they have received in the past two years, according to a recent national survey [72]. However, some Americans don’t always get the care they need. In fact, adults get, on average, only 55% of the recommended care for many common conditions [2]. Examples of the percent of recommended care that individuals receive for some common health conditions are shown in Figure 7.

Underuse and overuse

Striking the right balance between too much and too little care is a great challenge. Vaccines, colonoscopies, complete preventive care for diabetes, treatment for depression, and medicines to prevent additional heart attacks are all underused – that is, not everyone who should receive these health care services actually receives them [73-76].

On the other hand, some health care services are used too much. Too many patients take antibiotics that will not help them when they have colds and other viruses, some surgeries have questionable benefit, and some physician visits are not needed [2, 77, 78].

Some medical services are used much more frequently in some areas of the United States compared to other regions of the country. This disparity may be due to the overuse of some types of care. For example, Medicare pays for more care per beneficiary in Miami than it does in Minneapolis [79]. However, there is no evidence that the patients in regions where they receive more care have better health outcomes or that they are more satisfied than others who receive less care at less cost [80, 81]. This means that we may be able to get the same results using less of some forms of health care and spending less money.

Medical errors

There are also serious concerns about safety and preventable errors that occur in the health care system. The Institute of Medicine has estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die every year as a result of medical errors – that’s more than the number who die every year from car accidents, or breast cancer, or AIDS [5]. Studies in the states of Colorado, Utah, and New York have all estimated that medical errors occur in 2-4 percent of hospitalizations [82-84].

- Some medical errors are serious enough to keep a patient in the hospital for up to 11 extra days, and the added expense may be as large as $57,000 per patient [85].

- Up to 7,000 patients die in a given year as a result of medication errors alone [86].

Spending vs. outcomes

In the United States, we’re simply not getting the biggest “bang for our buck.” The United States spends at least $1,800 per person more on health care than any other developed country, but our health outcomes are not always better than in the countries that spend less.

It is difficult to compare health care across different countries, because there are factors like environmental, cultural, economic, and population differences that can affect health and longevity. However, a recent study compared health care quality in five countries that share a lot in common in cultural and economic history (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States). It focused on 21 different measures, including:

- Survival rates for serious diseases;

- Avoidable health events and outcomes (such as cases of measles, suicide, and deaths from asthma); and

- Prevention efforts, including vaccination rates and cancer screenings.

While the United States scored highest on four measures of quality of care, it was ranked second or third for 10, and last on five measures [4]. For example, the United States was the only nation among the five to have an increase in the national death rate for asthma in recent years. Overall, the U.S. ranks 29th in the world for “healthy” life expectancy, a measure that indicates not just how long people are expected to live, but also how much of that life span is expected to be spent in good health [87].

End-of-life care

The “too much, too little” challenges in our health care system are perhaps best highlighted in end-of-life care. For many Americans, this care can be expensive, of poor quality, fragmented, and often does not reflect the wishes of those who are dying and their families.

For example:

- More than half of Americans say that being able to be at home when dying is important, but only 15 percent of Americans die at home [8].

- 93 percent of Americans believe that being free of pain is important, but only 30 to 50 percent achieve this objective [8].

In many cases, doctors do not know with any certainty when a patient is going to die; it is not always possible to plan a “good” death at home [8]. However, the problems surrounding end-of-life care reflect some of the structural problems in the way we deliver and pay for medical care. The American health care system is better geared toward treating acute conditions [88]; as a result, many dying patients undergo medical interventions they may not need or want.

Insurance rules also limit access to the right kind of care for the dying. For example, Medicare limits enrollment in hospice services to those certified as being expected to live less than six months, a prognosis that is difficult to make, and which excludes patients who may be near death for longer than this arbitrary time frame.

Another reason the American health care system is ill-equipped to facilitate a “good death” is poor communication between patients and doctors in the last year of life [89]. And, because the needs of the dying straddle different care providers and health care settings, coordinating care among hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and family members can be very difficult. If this coordination falters, patients might be faced with interpreting different diagnoses, using services and processing information on their own. In addition, there is a shortage of caregivers, both paid and unpaid, and critical non-medical assistance, like helping patients get their affairs in order, is often absent. [90]

It has been estimated that last-year-of-life expenses constitute 22 percent of all medical expenditures. Changing the way that this care is delivered may not necessarily reduce these costs, because high-quality care that effectively manages pain and serious physical and mental impairment can be expensive [91], but it would be an important step in getting better value from our health care system, and better assuring ourselves humane and respectful assistance at the end of life.

Disparities are pervasive.

The American health care system gets poor marks for ensuring quality care across racial and ethnic lines. According to the 2005 National Healthcare Disparities Report, there is consistent evidence of differences in quality of care and health outcomes related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. The report found that, among the quality measures evaluated:

- African Americans received poorer quality of care than whites for 43% of the quality measures used.

- Asians received poorer quality of care than whites in about 20 percent of the quality measures used. American Indians and Alaskan natives received poorer quality of care than whites in almost 40% of the measures.

- Hispanics received lower quality of care than non-Hispanic whites in a little more than half of the quality measures used.

- People below the poverty line received lower quality of care in 85 percent of the quality measures used [39].

Reasons for these disparities are varied. Factors such as education and insurance coverage are intertwined with ethnicity and poverty. Poor communication between patients and providers can also lead to inappropriate care or unfavorable outcomes. For example, one study found that doctors were less likely to engage African American patients in conversation, and the tone of visits with African American patients generally was less friendly than with white patients [92]. Because more active participation of patients in conversations with their doctors has been linked to better treatment compliance and health outcomes, this could indicate that poor doctor-patient communication may be partly to blame for some racial disparities in health care.

V. Access Problems: Not Getting the Health Care You Need

“Hurricane Katrina has exposed another major weakness in our health care system. That is, our inability to assure even the basic needs related to health care are available to individuals and families who have been displaced from their communities and relocated all across the country.”

— Aaron Shirley

Getting the right care at the right time is not just an issue of cost. Sometimes, the greatest challenge to patients isn’t accessing good care – it’s obtaining any care at all. Affordability is key, but other factors come into play, including the availability of physicians and other health care professionals, hospitals and other health care facilities, and also people’s ability to get to these services, and to be treated appropriately when they get there.

Availability of services

While most Americans get health care when they need it, the availability of services varies a great deal across the country. Shortages of health professionals or facilities can occur because there are not enough people to support full-time medical practices, or even if there is a large enough population, people may have insufficient financial resources or insurance coverage to support providers’ practices. The lower rates (compared to Medicare or private insurance) that state Medicaid programs pay physicians could also limit people’s ability to find doctors [93].

In Mississippi, for example, more than half of the doctors are located in four urban areas in the state. In the rest of the state, including most of the rural, low-income areas, there are few, if any, doctors. Only 11 of 82 counties in Mississippi have enough doctors to meet the Council on Graduate Medical Education’s standards, and about 1 million people (one-third of the state’s population) live in counties that are classified as “underserved” [94]. But even when there are doctors and clinics in an area, people may not be able to get to them because of physical or financial challenges.

In some areas of the country and among some specialties, medical malpractice issues are contributing to access problems. Some doctors are choosing not to practice or not to care for the sickest patients because malpractice premiums and their perceived risk of being sued are higher [65]. Although malpractice legal costs and payments represent less than half of one percent of total health spending in the U.S. [64], for some doctors, fear of malpractice suits and the high cost of malpractice insurance are causing great concern [65].

Continuity of care and convenience

Although most Americans have a usual place to go to for health care, more than 15 percent of us don’t. Young adults and Hispanic Americans in particular are less likely than others to have a usual place to go for medical care [22]. Being a “nomad” in the health care system can mean diagnoses are missed, chronic conditions left unmanaged, and services duplicated, resulting in poorer health outcomes.

People without a regular place to go for care may rely more on hospital emergency departments (ED) for non-urgent care. Frequent use of EDs could also signal problems with the availability of routine health care services in the community.

- About 30 percent of all ED visits are for problems which are not urgent [95].

- Between 1993 and 2003, the rate at which Americans used EDs increased by about 26 percent [95].

- The rate of ED use among African Americans in 2003 was 89 percent higher than for whites but only slightly more likely to be for non-urgent problems [95].

- The rate of ED use among Medicaid recipients was higher than for

people with private insurance, Medicare, or no insurance coverage

at all, and also somewhat more likely to be for non-urgent problems

[95].

Another part of good access to health care services is ensuring ease of use. Not being able to get appointments when you need them, enduring long waiting times for visits, or not getting information about test results can all create barriers to getting the right care. All of these factors can contribute to disparities in access to care, just as they can to disparities in quality. The 2005 National Healthcare Disparities Report found pervasive differences in access to care across racial, ethnic and economic lines:

- African Americans had worse access than whites in 50 percent of the access measures used.

- Asians had worse access in a little more than 40 percent of the measures used. American Indians and Alaskan natives had worse access in half of the measures.

- Hispanics had worse access in about 90 percent of the measures.

- People below the poverty line had worse access to care in 100 percent of the measures used [39].

Millions don't have coverage.

“My son was born prematurely. He stayed in intensive care for six weeks. We didn’t have health insurance, so not only were we very worried about this sick baby, but we were worried about how we were going to pay for this. The bill was far more than what we would make even in a year. My son, who was later diagnosed with cerebral palsy, required 24-hour care the entire time he was growing up and was often very sick. I spent my days at home with him while my husband worked at the auto body shop. I waited tables at night to make ends meet.”

– Deborah Stehr

For most Americans, the overriding threat to getting the care they need is being able to pay for it. In 2004 245.9 million people had some form of health insurance coverage and in 2005 247.3 million people had some form of health insurance coverage. While the number of people with health insurance has increased the number without health insurance has also increased from 45.3 million people in 2004 to 46.6 million in 2005. [52]. Affordability is a powerful determinant of insurance status for adults. For some of us, the costs of needed medical care could lead to financial ruin. This is partly because an increasing number of Americans lack any type of health insurance. In addition, an increasing number have insurance that provides limited coverage that increases their out-of-pocket expenses.

| What is health insurance? In the United States, health insurance often covers a blend of predictable and unpredictable kinds of health care. As such, many people draw small amounts from the pool of insurance dollars every year, a few draw large amounts every year, and others draw large amounts just a few times over their lifetimes. It helps to think of health insurance in the same way you think of other kinds of insurance, like homeowners’ insurance, but there are important differences. People know that there is only a small risk that their house will burn down, but they buy insurance every year so that they are protected if the unthinkable happens. Some health problems—for example, injuries from car accidents or having a premature baby—do not occur very often but can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars when they do. Just like homeowners’ insurance, when a lot of people buy health insurance, the costs for these rare, expensive events are spread out over the large group of people who bought policies, reducing the cost to the unlucky few who actually need the help in a given year. In this way, health insurance is a transfer of money from those who don’t get sick or injured this year to those who do. The people who need care vary from year to year. Most of us will receive funding from that pool of money at some point during our lives. In contrast, however, some health care costs are routine and predictable, like annual physical exams or teeth cleaning, or medicines to treat chronic diseases. When the need for care is more predictable, people often think of insurance as a prepayment for something they are pretty sure they will need to use on a regular basis. If people decide to buy health insurance only when they know they are likely to need it, the costs can’t be spread out among policyholders, because everyone is using services, and the costs of policies can become high. |

People who do not qualify for employer-based health insurance or public

health insurance like Medicaid and Medicare may buy a health plan on

their own through a private insurance company. However, the individual

health insurance market is still relatively small and premiums often

are prohibitively expensive (several hundred dollars a month or more).

In most states, insurers can charge more or refuse to cover people with

pre-existing medical problems.

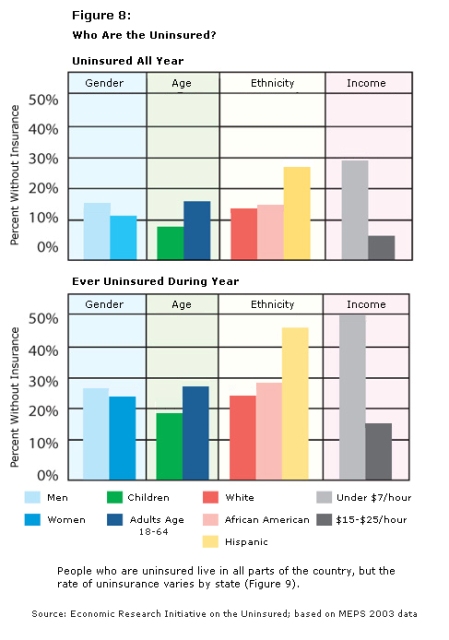

Estimates of the number of uninsured Americans are measured in different ways. As stated earlier, 46.6 million Americans lacked health insurance at a point in time in 2005[52]. Yet, one national survey conducted in 2004 estimated that over 51.6 million Americans experienced a spell of “uninsurance” over a one-year period [96], and 29 million had been uninsured for more than a year [96]. Hispanics, non-citizen immigrants, and self-employed adults are more likely to be uninsured over an entire year. [9] (See Figure 8).

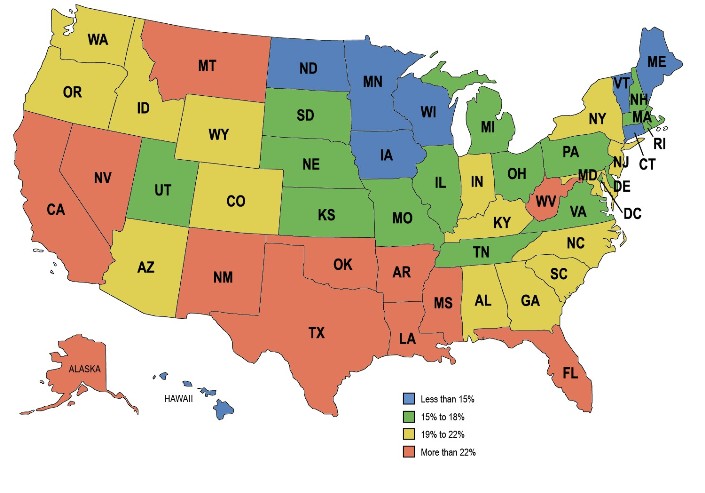

People who are uninsured live in all parts of the country, but the rate of uninsurance varies by state (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Percent of People* Uninsured Varies From State to State, 2003-2004

* Adults age 19-64.

Sources: Urban Institute and Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured estimates based on the Census Bureau's March 2004 and 2005 Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplements).

The likelihood of having insurance also is affected by the following factors:

- Type of employment – The likelihood that

a person or family will be covered through an employer depends on

the kind of job the employee has and the size of the firm in which

they work. Employers in the service and retail industries are less

likely to offer health insurance coverage. Employees working in these

industries also pay more in premiums than employees working in goods-producing

industries. Only half of firms in the Mountain region (Arizona, Colorado,

Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) offer coverage,

whereas three out of four firms in the East North Central region (Illinois,

Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin) do [97].

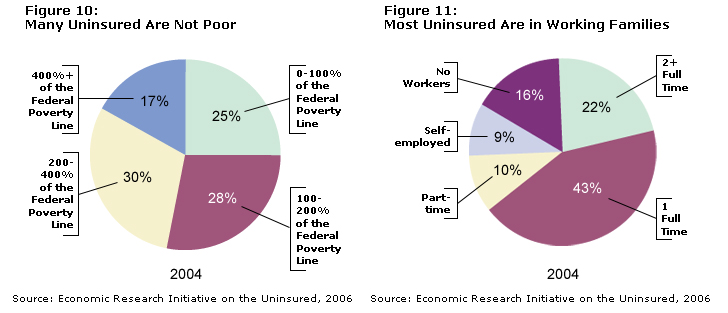

Even though most adults with health insurance obtain it through an employer, many people who do work are uninsured. In fact, two out of three people who are not insured are in a family with one or more full-time workers. Three out of four are in families with incomes greater than the poverty line [9]. Many simply cannot afford health coverage when it is available, and some choose not to buy it (Figures 10, 11).

- Health status – Pre-existing health conditions affect whether people can get health insurance and how much they pay for it. Private insurers will often not sell to or will require very high premiums from individuals with pre-existing health problems. Many jobs have six month or longer waiting periods before the insurance will cover any pre-existing conditions, and some insurance plans charge higher rates for all care related to pre-existing conditions.

- Age – Young adults are less likely than people ages 35 to 54 to enroll in a health plan offered by an employer or to work for a firm that offers one [9]. Although large employers (200 or more employees) are more likely than smaller ones to offer retiree health benefits, the percentage of large firms offering such benefits has dropped from 66 percent in 1988 to 33 percent in 2005 [46].

- Ethnicity – Hispanics are three times as likely as whites to be uninsured [9].

- Eligibility for public programs – One-fourth of children in families below the poverty line are without insurance, but only 8 percent of children below the age of 6 are without coverage, reflecting to a large degree their eligibility for Medicaid or SCHIP.

(Note: percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding)

Sudden changes can eliminate coverage

Just as we are all at risk for developing sudden health problems, it can be difficult to predict when someone might lose their health insurance coverage. Even with existing protections provided by federal law, people can lose insurance coverage for several reasons:

- A change in their firm’s benefits policy or a job change;

- The worsening of a chronic condition or the onset of a new illness or serious injury;

- A small increase in income or a change in marital status, which can cause people covered by Medicaid to lose their eligibility.

Sometimes the very things that cause us to need services may diminish our ability to pay for them. For example, when people develop diseases such as cancer or diabetes, get into serious car accidents, or give birth to babies who need special care, they may become unable to hold a full-time job, losing employer-sponsored health insurance as well as income.

No insurance = less care and more problems

While most Americans are able to get the care they need, people who are sicker, have lower income, have less education, and who do not have health insurance are more likely to delay care or fail to get care altogether because they cannot afford it [10].

- In 2004, about one in 20 Americans reported that costs prevented them from obtaining needed care, and this proportion has been growing since 1998.

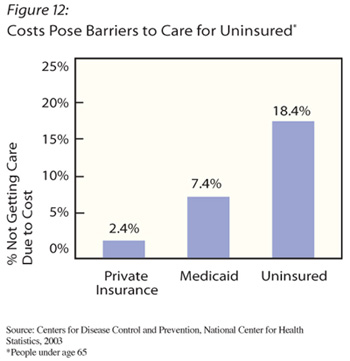

- Uninsured Americans are nearly eight times more likely than Americans with private health insurance to skip health care because they cannot afford it (See Figure 12).

- Half (49 percent) of uninsured adults with chronic health conditions go without health care or prescription medicines they need because of cost [98].

- Seniors who bear more of the cost of their health care use fewer services, sometimes resulting in poorer health [99].

Not getting care when it’s needed can cause serious health consequences. A recent study found that, of people who get into car accidents, those who are uninsured receive 20 percent less treatment and are more likely to die from their injuries than people with health insurance coverage [100].

If you do not have health insurance and need medical care, you also may experience other problems. Getting sick may cost you your job, and if not, you may lose many days of work and experience reduced productivity. This adds to the cost burden for our country’s health care system; for example, it is estimated that indirect costs for people with diabetes amount to $40 billion a year; for those with arthritis, indirect costs are over $86 billion a year [101, 102].

It could be anyone - even you.

Even if you do have a health insurance plan, you might not necessarily have adequate coverage. In general, “underinsurance” refers to the lack of coverage for different types of needed care that someone will not purchase without financial assistance.2

Common examples of services for which people tend to lack adequate insurance include various kinds of preventive care, mental health care, prescription drugs, and physical therapy. Policies that do not provide generous coverage for services that may be expensive but very important may also be seen as underinsurance, particularly for low-income families. For example, a policy with a $5,000 deductible or a 20-percent co-payment could result in bills of several thousand dollars for even a short hospital stay, which might be difficult for a typical low-wage worker to afford.

And, if you do have adequate health insurance, there’s no guarantee your coverage will continue. The millions of Americans who move in and out of health insurance coverage each year illustrate the fact that even those with coverage have no guarantee that coverage will continue indefinitely.

VI. What is Being Done?

“I think we've got to watch out that we don't throw out the baby with the bathwater here in dealing with American medicine.”

– Frank Baumeister

As we have discussed, there are serious problems with America’s health care system: sharply rising costs, unreliable quality, and gaps in access to affordable health care – all of which pose certain risks to every American and the country as a whole. But as Frank points out above, we can build on what works well to find health care that works for all Americans.

Cost, quality, and access are not independent of each other. Our health care system is a lot like our natural environment – an “ecosystem,” in which any significant change in one area has ripple effects throughout the others.

Comprehensive approaches.

In our work to date, we have heard about efforts by states, communities, and large health care systems to deal with the interrelated health system issues of cost, quality, and access. The preliminary hearings we held around the country taught us about interesting examples. These are not the only examples but they illustrate both the complexity and the challenges involved in improving health care. Such programs require ongoing financial commitment and administrative expertise across a number of organizations. Further, the programs we heard about are new, so we do not know yet how well they will work over the long-term. Because these programs were designed to work in specific localities, we do not know whether the programs would fit, or work successfully in other areas or communities. Nevertheless, they represent important examples of the types of initiatives we must learn from to arrive at measures to improve the larger health care system.

| Dirigo Health. Through legislation enacted in

2003, the state of Maine is attempting to deal with the intertwined

issues of cost, quality and access. Their plan illustrates how the

issues are interconnected. To increase access, Maine has expanded its Medicaid program and developed a new insurance product, Dirigo Choice, targeted to small businesses, the self-employed and eligible individuals. Employers pay 60 percent of costs and monthly premiums and deductibles for people with incomes below 300 percent of the Federal Poverty Level are discounted. These subsidies are financed in large part by savings resulting from cost control measures and from reductions in health care providers’ bad debt and charity care. The Maine Quality Forum functions as a quality watchdog providing more information to citizens about costs and quality. It also will adopt quality and performance measures and promote evidence-based medicine and best practices. To control costs, capital expenditures for hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers and doctors’ offices across the state have been put on a budget, and spending on new technology in these settings is highly regulated. |

Ascension Health, a large non-profit health

system, has initiated several collaborations between its partners

and local communities to improve care and access for the uninsured.

Twelve partnerships already exist around the country; each works

to improve access through five steps:

2. Filling in gaps in the existing safety net, especially regarding mental and dental health; 3. Improving the coordination of care for the uninsured; 4. Recruiting physicians to voluntarily provide primary and specialty care for uninsured patients; and 5. Achieving sustainable funding to support these activities. Ascension Health has already provided $7 million to these community partnerships in matching grants. |

Targeted approaches

We also heard about other programs that are more narrowly focused. For example, some are designed specifically to control health care costs; other approaches focus on quality improvement; and still others concentrate on improving access to primary care services or expanding health insurance coverage to a greater number of people. While the goals of these programs might complement each other, they can be quite different in design and implementation. In addition, strategies that lead to lower insurance costs or more insurance coverage for some people might lead to higher premiums for others, or to higher public spending.

Controlling health care costs

Several initiatives have been designed by Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, health plans, and employers to control system-wide costs. These strategies work in one of three ways: by influencing the amount of health care services we use, the types of services we use, or the price of those services.

Although what is considered “discretionary” or “unnecessary” is frequently subject to debate, some insurers limit the use of certain services sometimes by giving patients and doctors financial incentives to reduce their use. The rationale behind this approach is that some health care services are overused and do not contribute to better health:

- Some insurance plans and employers have increased the amount that patients must pay out of pocket for care that might be considered cosmetic or otherwise not medically necessary. The goal is to make patients aware of the costs and enable them to purchase their health care on a more informed basis.

- Both public and private insurers have placed limits on coverage

for some types of medical equipment, such as certain motorized chairs

or scooters, or on the number of new eyeglasses that will be covered

in a year. Limits also may be placed on the number of nursing home

beds or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines that are allowed

in an area. Some insurers pay specific types of providers a fixed

amount for each patient independent of the number of services used,

putting pressure on them to reduce the services offered.

A small but growing number of employers are changing insurance coverage in an effort to give employees more financial stake in choosing their care. Health savings accounts (HSAs) and other high deductible options are prime examples. In HSAs, employees can set aside a fixed amount of money, tax free, to pay for their health expenses; they get to keep what they don’t spend and use these funds to pay for health care the next year. Both HSAs and other high deductible health plans that do not have this savings feature require employees to pay for the first $1,000 or more of their health care costs each year before their health insurance covers the rest.

Because employees have to pay for all their care out-of-pocket until they reach the deductible, they may be less likely to use some health services. Shifting costs to employees also means that people with more health care needs will have significant out-of-pocket costs. Further, if those who sign up for these high deductible plans are mostly healthy people with limited health care expenses, their premiums will remain low, while sicker people in conventional plans may have to pay higher premiums. HSAs could, therefore, reduce health care costs for some people, while increasing costs for others.

Some health plans offer financial rewards to patients and health care providers for using less costly options that may be just as effective as more expensive alternatives under some circumstances. Health plans frequently require patients and health care providers to try less costly treatment options first, moving on to more expensive options only if they are needed. One clear case is health plans that promote the use of generic medicines that are substantially less expensive than the chemically equivalent brand-name prescription drugs. As an example, the brand-name allergy medication Allegra® can cost nearly $90 for 60 pills, but its generic equivalent sells for $38 – less than half of the name-brand price [105]. In 2000, $229 million could have been saved in Medicaid spending if generic drugs had been used more widely.

To encourage people to use generic equivalents of prescription drugs, many health plans require patients to pay smaller amounts out of their own pockets for generics than for brand-name drugs. In fact, many health plans offer “tiered” prices for prescription medicines, in which co-payments or coinsurance are highest for specialty drugs, next highest for brand name drugs, and lowest for generic drugs.

Increasing efficiency: costs and quality

It is not always clear how incentives that affect cost and payment to health care providers affect quality. Some approaches being tried are trying to improve efficiency by decreasing cost and improving quality. For example, “pay-for-performance” programs pay hospitals, physicians and managed care plans more when they provide cost-efficient, high-quality services, such as providing recommended health screenings, or when a high proportion of their patients are satisfied with their care, or receive appropriate care for diabetes or heart disease [1]. Medicare has started a pilot project in which it will pay bonuses to hospitals that have the best performance in the treatment of heart attacks, heart failure, and pneumonia, as well as the top results for heart surgery and hip and knee replacements [1].

The Leapfrog Group, made up of over 170 organizations and companies

that buy health care, is working with its members to reduce preventable

medical mistakes by rewarding providers for improving affordability,

quality, and safety, and providing information to consumers to help

them make more informed health care choices[116]. Some public and private

insurers have made performance ratings of physicians or hospitals available

to the public [104]. Similarly, some health plans have asked consumers

to pay more in premiums or face higher co-payments if they choose less

efficient or lower-quality health care providers.

| Culinary Health Fund provides health

insurance to about 120,000 Las Vegas workers who are members of

Culinary Local 226 (part of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees

International Union) as well as their families. Employees do not

pay a premium for coverage – employers pay 100 percent of

the cost. Benefits include a free pharmacy of certain generic drugs as well as low co-payments for physician visits, medical services, and prescription drugs. To control costs and provide incentives for better quality care, the Culinary Fund has, since 2002, rewarded physicians for providing high-quality care through a pay-for-performance system that uses semi-annual performance assessments that analyzes information on 32 evidence-based quality indicators, and pays bonuses to physicians who provide high-quality care. In addition, Culinary Local 226 and employers work together to negotiate prices with health care providers. The Fund also requires that pharmacists use generic drugs whenever possible, and steers employees’ spending with tiered payment strategies for benefits such as prescription drugs. Generic drugs have the lowest co-pay ($5), covered brand-name drugs listed in the plan’s formulary have a $13 co-pay, and covered brand-name drugs that are not listed in the formulary have the highest co-pay of $28. To discourage use of emergency department (ED) care when it is not truly needed, the plan charges a patient making a non-emergency visit to the ED a $125 co-pay plus 40% of the visit’s full cost. In contrast, a true emergency visit costs the patient only the $125 co-pay. |